Editor's note:

The United Nations has officially designated 44 Chinese traditions as world cultural heritage. This series examines how each of them defines what it means to be Chinese.

Yunjin, or "cloud brocade," takes its name from its shimmering, cloud-like iridescence.

"One inch of Yunjin brocade is worth one inch of gold."

This old saying captures the extraordinary value of a textile that dazzled emperors, inspired artists and became a pinnacle of Chinese craftsmanship.

The intricate weaving requires two artisans to work in perfect coordination. Even after eight hours at the loom, they can produce only 5 to 6 centimeters of fabric.

Known as Yunjin, or "cloud brocade," the silk takes its name from its shimmering, cloud-like iridescence. Originating in Nanjing, east China's Jiangsu Province, it stands as one of the finest achievements in the country's brocade tradition, with a history spanning more than 1,600 years.

The craft can be traced back to AD 417, when the Eastern Jin Dynasty (AD 317-420) established a bureau in Jiankang — modern-day Nanjing — to oversee brocade weaving. Over centuries, Yunjin absorbed techniques from across China and flourished in the Yuan (1271-1368), Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

By then, Yunjin was reserved for emperors and the imperial household, earning the title "the crown of brocades."

Yunjin weaving requires two artisans to work in perfect coordination.

According to the Nanjing Yunjin Museum, the Ming and Qing periods perfected weaving with gold thread. Just 1 gram of gold could be hammered into foil only 0.12 micrometers thick, covering nearly half a square meter.

Craftsmen flattened the foil on paper, sliced it into strips, and twisted them with silk threads to create the luminous patterns.

Yunjin is woven on towering wooden drawlooms — nearly 6 meters long and 4 meters high — assembled from almost 2,000 interlocking parts. Two artisans share the work: one above lifts warp threads in sequence while the weaver below passes the shuttle through.

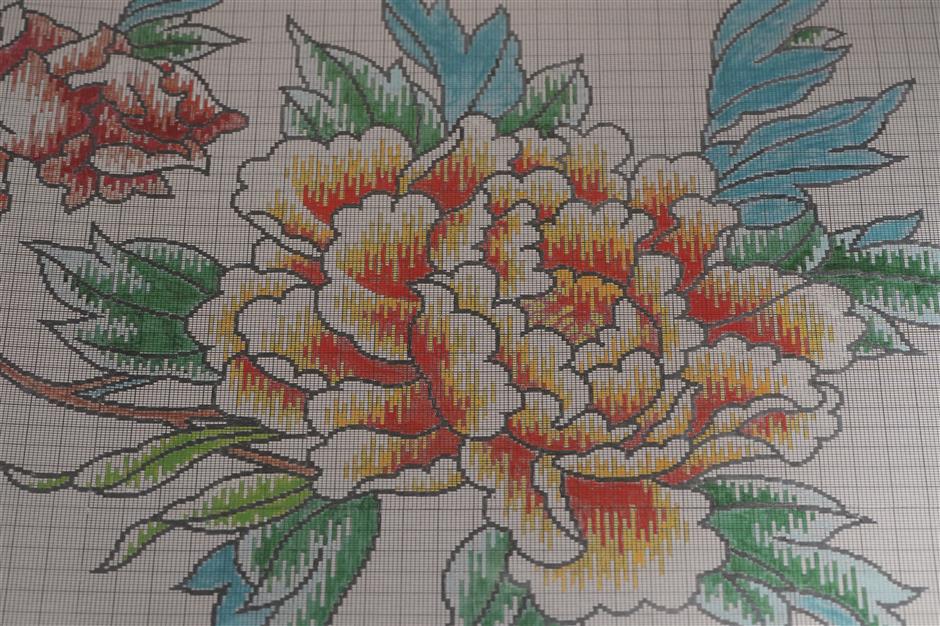

A Yunjin artisan plots a motif of peony on gridded paper known as yiyang tu.

Design begins before the loom, with artisans plotting motifs on gridded paper known as yiyang tu. Each square represents a thread.

The next step, tiaohua jieben, translates the design into bundles of threads linked to the loom, a process often likened to programing a computer by hand. Some call it the world's earliest form of coding: When warp lies above the weft, the motif appears; when it lies below, it disappears — like 1 and 0 in binary.

Materials add another layer of brilliance. In addition to silk, artisans use gold and silver threads, copper wires and even peacock feathers. Peacock plumes create the shimmering greens of imperial robes, while gold threads add grandeur.

Common motifs include dragons, phoenixes, clouds and peonies — symbols of prosperity and good fortune. Colors favor strong, auspicious tones such as red, yellow, blue, green and purple, often enhanced with lavish gold.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, Yunjin reached its zenith. The Qing court established the Jiangning Weaving Bureau in Nanjing to supervise production. At its peak, the industry operated more than 30,000 looms and employed over 100,000 workers, making it Nanjing's largest handicraft sector.

But the decline of the Qing Dynasty brought hardship. By the mid-20th century, fewer than five artisans still practiced the techniques.

Shimmering silk threads are used in Yunjin brocade.

To rescue the tradition, the Nanjing Yunjin Research Institute was founded in 1957, followed by the Nanjing Yunjin Museum, China's only museum dedicated to the craft. Their mission: to preserve, study and revive Yunjin brocade.

In the 1980s, researchers reconstructed the delicate Western Han (206 BC-AD 25) gauze gown unearthed from the Mawangdui tombs in central China's Hunan Province. The gown weighs just 49.5 grams.

A replica of the gauze gown unearthed from the Mawangdui tombs in central China's Hunan Province.

They also recreated the peacock-feather dragon robe from the tomb of Emperor Wanli of the Ming Dynasty.

In 1958, the excavation of the Dingling Mausoleum in Beijing brought to light Emperor Wanli's dragon robe, a masterpiece that immediately drew attention. Yet after being unearthed, the robe carbonized quickly. Its colors faded beyond recognition, and parts were badly damaged.

The robe was later confirmed by experts as a pinnacle of Nanjing Yunjin craftsmanship. The task of reproduction then fell to the Nanjing Yunjin Research Institute.

The challenge was immense. The original robe used large amounts of gold thread and peacock feather yarn. To make gold thread, artisans hammered heavy bullion more than 30,000 times into gossamer-thin foil. Peacock feathers, collected from places like southwest China's Yunnan Province, were hand-spun one by one into threads. More than 300 meters of peacock feathers were needed for the robe.

After five years of painstaking work, the reproduction was completed in 1984, bringing back to life the dazzling brilliance of Emperor Wanli's dragon robe.

Nanjing Yunjin Museum is China's only museum dedicated to the craft of Yunjin brocade.

In 2009, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization inscribed Nanjing Yunjin brocade on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Today, the Nanjing Yunjin Museum preserves looms, fabrics and archives while training new generations of artisans. Visitors can watch masters at work, gaining a glimpse of a process unchanged for centuries.

Yunjin brocade also inspires contemporary fashion. In 2010, Chinese actress Fan Bingbing appeared at the Cannes Film Festival in a Yunjin gown by designer Laurence Xu.

Named "Auspicious Cloud of the Orient," it featured dragon and cloud motifs woven with Yunjin brocade techniques. The gown later entered the collection of London's Victoria and Albert Museum, symbolizing how an ancient craft can meet global fashion.

Each inch of Yunjin brocade is a record of history, artistry and devotion. To hold a piece is to hold not only silk but the ingenuity of countless hands.