On June 29, Xuzhou football fans take a special "fan train" to travel 150 kilometers to Taizhou for a Su Super League match.

"No rigged games, only blood feuds."

In China, an amateur football league, featuring everyone from teachers and waiters to couriers, IT guys and even high schoolers, is blowing past Trump, trade wars and Labubu on domestic trending lists.

Tickets are as scarce as FIFA World Cup seats. Italian legend Ambrosini even sent in his resume, angling for a summer stint, and beer giant Heineken has signed on, too.

To truly understand the spirit and opportunities of China today, you have to look to the fiery rivalries that fuel this grassroots league.

Battle for the top seat

On the sweltering night of July 5, with temperatures hitting a scorching 40 degrees Celsius, a record 60,396 fans erupted in roars as two teams fought tooth and nail right down to the final minute.

The match between the cities of Nanjing and Suzhou was part of the sixth round of the Su Super League, officially known as the Jiangsu Football City League. The league features amateur teams from 13 cities in Jiangsu Province, a major economic region in East China.

The season runs from May to November, and of the 516 players participating this year, only 29 are professionals.

Rumor once had it that the championship prize was rice and cooking oil, typical promotional gifts from the Bank of Jiangsu, the league's main sponsor. But what really stoked the intensity was the deep-rooted "rivalry" between the two cities.

Just as Milan looks down on Rome, and New York nurses a grudge against Washington DC, Suzhou has long been viewed as a rival nipping at Nanjing's heels for the title of provincial capital.

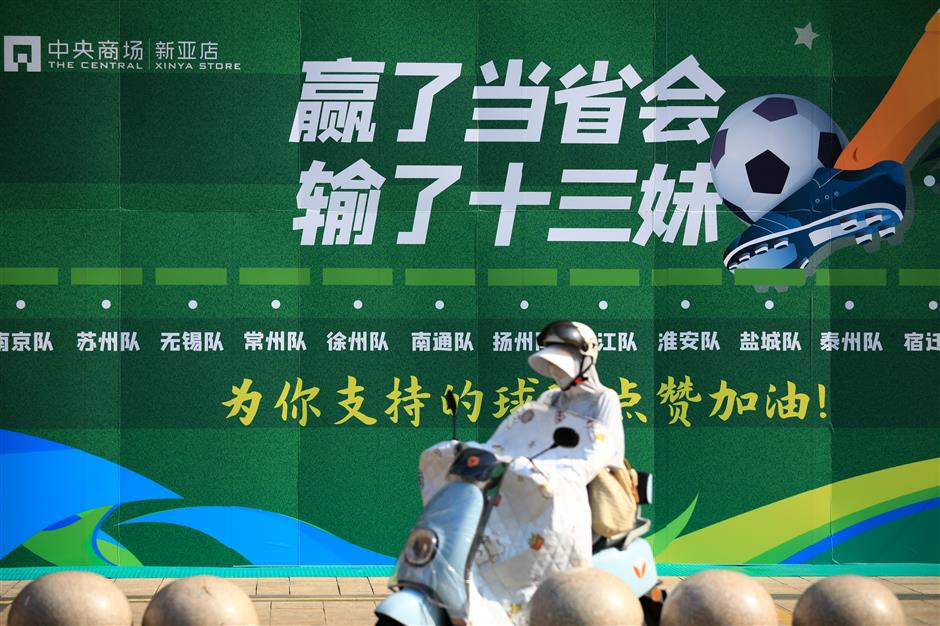

A street billboard in Huai'an reads: "Whoever wins becomes the provincial capital; whoever loses stays the provincial underdog."

The rivalry stretches back centuries. Steeped in history and cultural cachet, Nanjing, once the capital of six dynasties, wields significant political clout in southern China, while Suzhou, by contrast, has long reigned as the region's commercial juggernaut.

Today, while in most Chinese provinces the capital city also dominates economically, Jiangsu is the exception. Its GDP reached 13.7 trillion yuan (US$1.96 trillion) last year, roughly on par with Russia's entire economy. Suzhou alone contributed nearly 20 percent, with a GDP exceeding that of Finland. Nanjing was in second place, close to New Zealand's level.

So when Suzhou took on Nanjing in the Su Super League, this match was jokingly framed as a showdown for provincial supremacy. Before kickoff, Suzhou's billboards boldly declared: "First in football, first in GDP." Nanjing responded with banners in subway stations saying: "Petite Suzhou, money doesn't solve everything."

More than 688,000 fans scrambled to snap up tickets for the match online. With odds of less than 9 percent, scoring a ticket was nearly as tough as getting one for the Qatar World Cup.

Japanese documentary director Ryo Takeuchi, who lives in China, was in the stands for the match.

"I've watched the World Cup and J-League," he posted on social media, "but I've never seen this many people at a match. The atmosphere was even more passionate than the World Cup."

This passion isn't just for one match. That week, the league drew an average crowd of over 39,000 per game, rivaling the English Premier League and Bundesliga.

The league's success boils down to a popular online saying: "No rigged games, only blood feuds."

A screenshot from a viral video where each team is personified through local specialties. Taking center stage are a duck and a crab – representing Nanjing and Suzhou, famous for salted duck and hairy crab.

A province fueled by rivalries

Jiangsu is practically hardwired for local rivalries. Roughly the size of Iceland, it's crisscrossed by rivers and canals – geography that has nurtured a rich tapestry of dialects and cultures. Long a strategic military crossroads in ancient times, those old feuds still simmer today, serving as the nourishment for creating topics to promote the league.

Take Xuzhou and Suqian for instance – hometowns of Liu Bang and Xiang Yu, whose legendary clash unfolded over 2,200 years ago. Liu, the eventual winner, founded the Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD), a pivotal chapter that laid the groundwork for the ancient Silk Road. Xiang's poignant defeat gave birth to the enduring story "Farewell My Concubine," later adapted into a Cannes-winning film.

When these two cities face off, fans throw their support behind the teams with fierce pride. It's as if those ancient generals have been resurrected on the football pitch.

Perhaps such sense of competition has been driving the cities in Jiangsu in development in every sphere, ranging from economic and industrial growth, to industrial and tourism sectors.

Today, the province has developed into one of China's most balanced economies. Even its lowest-ranked city, Lianyungang, logged a GDP of over 466.3 billion yuan last year, outpacing many provincial capitals. Globally, it's closing in on Myanmar's.

Each city has carved out its own industrial niche. Even many county-level cities and districts pack an impressive economic punch.

Donghai County of Lianyungang is a global heavyweight in handmade press-on nails. Last year, its sales reached 8 billion yuan, with nearly 40 percent exported. Danyang of Zhenjiang produces more than half of the world's eye glasses. Kunshan of Suzhou, known for its electronics and equipment manufacturing, has stayed top of China's list of 100 richest counties for 20 years.

This prosperity and diversity have forged strong local pride. People rarely refer to themselves as "Jiangsu natives" – instead, they say "I'm from Suzhou" or "I'm from Danyang."

There is another saying that people from Kunshan never consider themselves Suzhou residents, unless "Suzhou takes down Nanjing in the league."

A Yangzhou player (in blue) battles for the ball during a match against Suzhou.

Jiangsu isn't always this fragmented. When rumors spread that China's men's national team, currently ranked 77th in the world, might get involved in the league, fans from every city banded together to say "Please don't." They were wary of scandals involving match-fixing of professional players.

In contrast, the Su Super League is not only genuinely competitive, but also showcases impressive skill.

Jiangsu's robust economy provides the resources to sustain high-quality grassroots football. The province boasts 1.36 football pitches per 10,000 residents on average, and every city has at least one stadium capable of holding 30,000 fans.

Many of the players come from over 200 youth training camps across the province. The top-ranked Nantong team, for example, includes 35 players who trained at a youth academy set up by a slipper factory owner.

Cheap seats, big impact

When the league first kicked off, it flew under the radar, with just six sponsors and average crowds of fewer than 8,000 per game.

But about two weeks into the season, on May 28, an article from Nanjing's official media ignited a surge in interest with a playful headline: "Competition First, Friendship Fourteenth." Official media from the other 12 cities quickly joined in, trading playful barbs and good-natured self-mockery.

Online discussions about the Su Super League soon surpassed 100 million views. Attendance has since grown nearly fivefold, and the league now counts 29 sponsors, including known brands such as JD.com, Taobao, Pizza Hut and Heineken.

A survey by China's National Bureau of Statistics shows that nearly 80 percent of the league's followers are not traditional football fans.

As players battled on the pitch, the cities vied off it with cultural events and tourism pushes.

Lianyungang's halftime show starred the Monkey King, a nod to the city's fame as the hometown of the legendary simian from "Journey to the West." Meanwhile, in Taizhou, 800 drones lit up the sky with a message: "A kid may choose one, I want both friendship and victory."

Xuzhou takes advantage of the team's match in Taizhou to hold a promotion event for cultural and tourism products.

Low ticket prices have made the league a powerhouse for local tourism. Backed by government subsidies and tax incentives, most tickets cost around 10 yuan, even cheaper than a cup of milk tea.

In host cities, fans can use their ticket stubs to enjoy discounts on local attractions, accommodations and meals.

Changzhou's "9.9-yuan ticket + pickled radish fried rice" deal doubled sales of the city's signature pickled radish. In Yancheng, home to Asia's largest coastal wetland, a "birdwatching + football" package racked up over 20,000 bookings shortly after launch.

Data from Meituan Travel and other platforms show that in host cities, hotel bookings, attraction tickets, and sales of local specialties, like Nanjing's salted duck and Huai'an's crayfish, surged significantly year-on-year last weekend, with 59-255 percent increases.

Nantong fans watched their team's match at a shopping mall on July 5.

A window into China's urban future

But the Su Super League is more than a local sensation. Behind Jiangsu's economic dynamism lies the greater Yangtze River Delta integration – China's most advanced urban cluster. Covering less than 4 percent of the country's land, it generates about 25 percent of its GDP.

The region comprises Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Anhui provinces and the city of Shanghai. Cities are closely connected through transportation. Every day, more than 2 million passengers travel by train within this cluster.

With a complete and integrated industrial chain, the region hosts many world-class manufacturing clusters.

Take the new-energy vehicle industry as an example. The Yangtze River Delta is home to headquarters, and key R&D or manufacturing bases for brands like Nio, BYD and Geely. In the first quarter of this year, the region churned out 1.11 million new-energy vehicles, accounting for over a third of China's total output, according to Xinhua Daily. As the saying goes, "Shanghai makes chips and smart networks, Jiangsu supplies batteries, Zhejiang specializes in die-casting, and Anhui assembles the cars."

Beyond industry, Zhejiang is emerging as a leading contender to produce the next Su Super League. On July 6, Zhejiang's grassroots basketball tournament, the ZheBA, officially began, with teams fielded by each of its 90 counties.

In terms of cultural diversity and balanced urban development, Zhejiang is on par with Jiangsu. As China's fourth-largest provincial economy, Zhejiang boasts deep-seated local pride and thriving county economies. Many county-level cities and districts turn out products that have made a name for themselves across China and even globally. For example, Yiwu, a county-level city under Jinhua, is known as the "capital of world's small commodities."

Over the next six months, ZheBA will feature matchups like the "Pearl Capital of China" facing off against the "International Textile Capital" and the "World Small Commodity Capital" going head-to-head with the "Hardware Capital of China."

One thing's certain: even the fragmented people of Jiangsu can agree on – Zhejiang folks are loaded!