Editor's note:

The United Nations has officially designated 44 Chinese traditions as world cultural heritage. This series examines how each of them defines what it means to be Chinese.

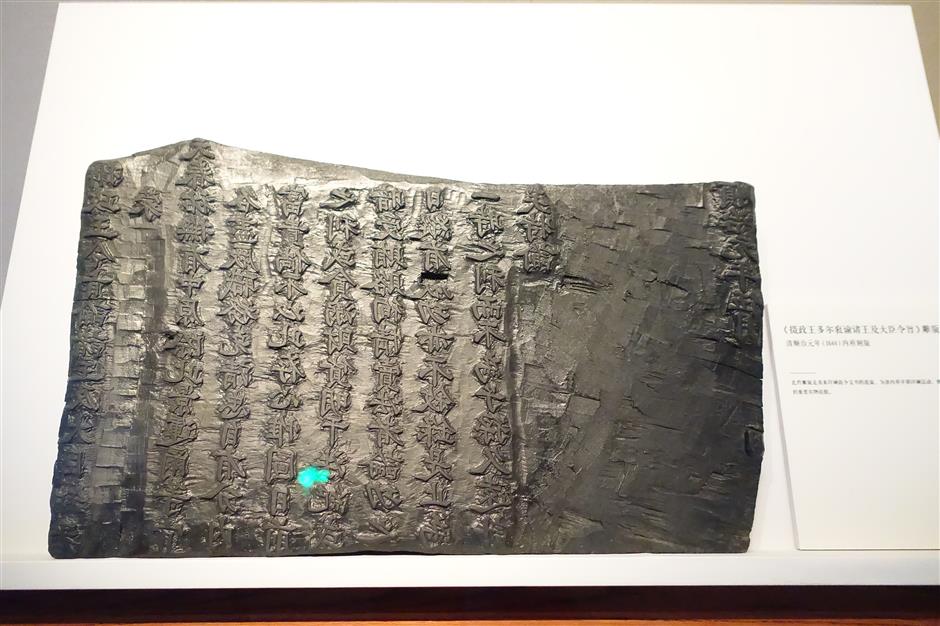

A woodblock featuring an imperial command issued by Dorgon, prince regent of the early Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), is displayed at the Palace Museum in Beijing.

A thousand years ago, Chinese artisans gave birth to one of the world's most transformative technologies — engraved block printing. With little more than paper, ink and carved wood, the technique allowed people to spread knowledge and culture in a much more efficient way than before.

The technique was added to the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization in 2009.

Collected by the Palace Museum, this Qing Dynasty woodblock bears engravings of Buddhist sutras.

From sacred texts to commercial books

The exact origins of Chinese block printing remain debatable. However, it is widely accepted that the technology matured during the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907).

In its early stages, block printing served primarily religious purposes. Monks and artisans used it to reproduce Buddhist sutras and sacred images. The famous Tang Dynasty monk Xuanzang, who traveled to India to study Buddhism and brought back 600 sutras in the 7th century, reportedly used special paper to print the image of Samantabhadra for his followers.

Block printing soon moved beyond monasteries. It was used to produce calendars, tax records and even early newspapers in the Tang Dynasty. The Kaiyuan Zabao, compiled during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, is considered by some scholars to be the world's first printed newspaper, even predating Germany's Relation by almost 900 years.

Very few Tang-era prints have survived. One exception is the "Great Dharani Sutra of Immaculate and Pure Light," which was found in South Korea's Seokgatap, a Silla Dynasty pagoda at the temple Bulguksa in Gyeongju. The work is believed to have been printed between AD 704 and 751.

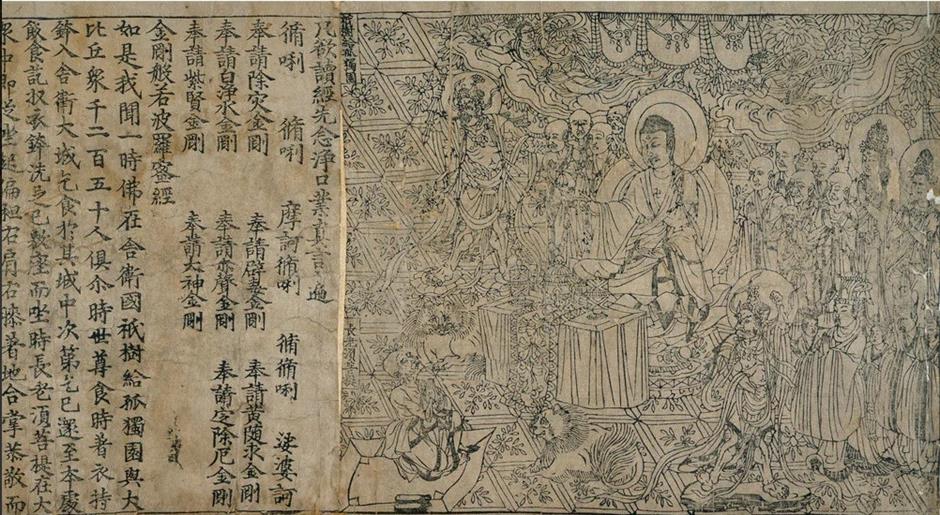

The “Diamond Sutra” print is currently housed in the British Library.

Another rare relic is the famous “Diamond Sutra,” which is the world's earliest dated printed book. The manuscript consists of a scroll, over 16 feet (4.8 meters) long, made up of a long series of printed pages. Printed in AD 868 and discovered in 1907 in the Library Cave at the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, northwest China's Gansu Province, it is now housed in the British Library.

The Library Cave at the Mogao Grottoes was discovered in 1900, with more than 60,000 cultural relics dating from the 4th century to the 11th century unearthed. It was one of the most important archeological discoveries of the 20th century.

However, the majority of the relics were later stolen by foreign explorers. The artifacts are now scattered across the world, with only a small portion remaining.

A life-sized recreation of the Library Cave at the Mogao Grottoes is on display at the Tianjin Digital Art Museum.

Block printing reached its technical peak during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Printing centers emerged in cities like Hangzhou and Chengdu. What began as a tool for religious and scholarly use evolved into a booming commercial industry. More people could now afford books, changing the way knowledge was consumed.

The Song Dynasty also saw a series of innovations. A new typographic style, the Song typeface, was developed to suit carving and mass reproduction. Book formats evolved from scrolls to stitched volumes and folding booklets, allowing for easier reading and better page alignment.

Color printing also emerged during the Song era. Craftsmen in Sichuan developed "set-block printing" where separate blocks were used for each color and printed in precise layers.

Illustration became another key feature. Early block-printed books included architectural drawings, religious images, geographical maps and artistic woodcuts.

In addition to wood, craftsmen in the Song Dynasty experimented with wax as a material to carve. Wax blocks were introduced to print urgent government decrees and examination results.

One of the grandest projects of the period was the "Kaibao Tripitaka," which was commissioned in AD 971 by Emperor Taizu of Song. Carved over 12 years in Chengdu, the Buddhist canon involved more than 130,000 carved woodblocks and featured 5,048 volumes.

Students in Fuzhou, east China’s Jiangxi Province, practice the art of woodblock engraving.

A delicate craft, a demanding process

Chinese block printing is labor-intensive and demands precision at every step. Artisans begin with selecting the right materials. The wood must be fine-grained and durable; the paper must be strong yet smooth to absorb the ink clearly.

The process of block printing involves three key steps: writing, carving and pressing.

Artisans write the text onto thin paper, which is pasted in reverse onto polished woodblocks.

Once dry, the carving begins. Craftsmen would use up to 30 different blades to remove the negative space around each character, leaving the strokes raised in relief.

The finished woodblock becomes a reusable stamp. Printers first brush ink across the carved surface, then lay paper atop it. A clean brush gently presses the paper to transfer the inked design. After printing each page individually, workers bind them into books.

A craftsman gently brushes the paper to transfer the inked design from the block.

A global influence

The impact of block printing was not limited to China. By the late 10th century, the technology had spread to the Korean Peninsula. In AD 993, the Song Dynasty court gifted a copy of the "Kaibao Tripitaka" to the Goryeo Dynasty, which sent craftsmen to China to learn the technique.

In the Islamic world, Persian merchants carried the technology westward along the Silk Road. By 1294, Persia, now Iran, had begun printing paper currency featuring both Chinese and Arabic scripts.

Even Europe felt its effect. European crusaders returned home with woodcuts, playing cards and printed texts, which laid the groundwork for Europe's own printing revolution centuries later.