It's 11pm, but the studio lights are still blazing. A young livestreamer sways to the beat alongside four other girls.

Hip rolls, hair flips, fingers grazing collarbones – the choreography has been drilled hundreds of times. On cue, they smile for the camera, bodies moving in perfect unison.

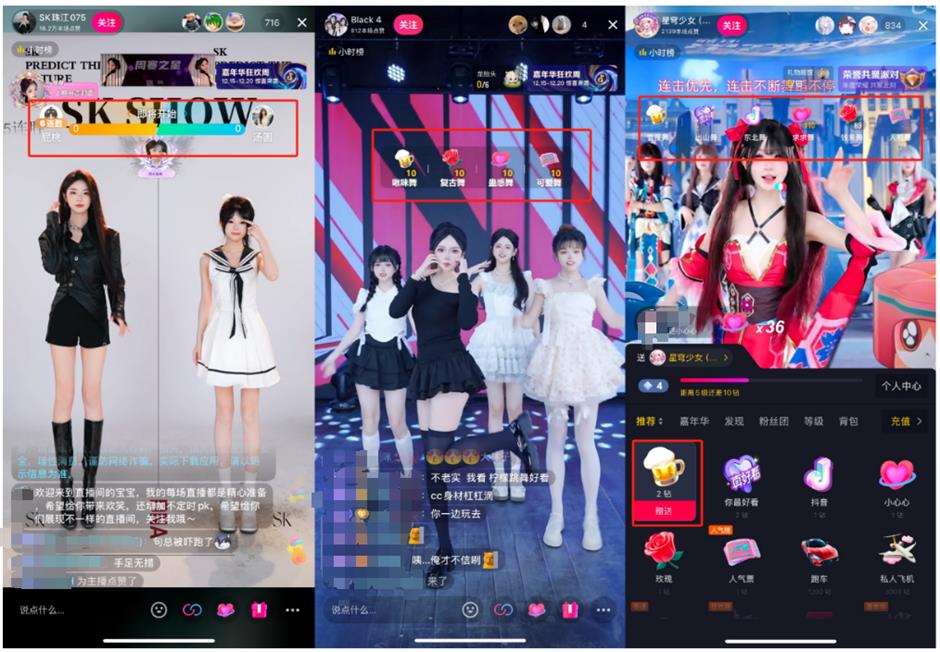

This is tuanbo – group livestreaming – where five to eight performers broadcast together, blending synchronized dances with mini-games and head-to-head battles. Every evening after 6pm, around 15,000 streams lit up the platforms, according to 36kr.com.

It's part talent show, part fan economy, with viewers holding the remote: every click, gift, and vote shapes the performance.

The promise of stardom

Once a quirky subculture, tuanbo has exploded into a mainstream phenomenon on China's short-video platforms. Professional dancers, theater graduates, even film school students are flocking to agencies in hopes of turning skills into digital stardom.

Stories abound of amateurs pocketing tens of thousands of yuan overnight, or forgotten reality-show contestants reviving careers through livestreaming. Recruiters dangle irresistible promises: low entry barriers, high pay, and the chance to "live your K-pop dream."

Even stars of Hong Kong's TVB channel, including Au-yeung Chun Wah, Ng Cheuk Hai, and Kwok Chun On, have joined the ranks of group livestreams. At the same time, some tuanbo guilds are recruiting directly on China's elite "211" campuses – evidence the trend has gone mainstream.

TVB stars, including Au-yeung Chun Wah, Ng Cheuk Hai, and Kwok Chun On, have joined the ranks of group livestreams.

The grind behind the glamour

The reality, though, is less glamorous. Schedules stretch to 10 hours or more. Salaries often fall far short of the hype. And with the rise of livestream guilds, disputes over unpaid wages, exploitative contracts, and sexualized content are rampant.

Li Li, 22, signed on after months of job hunting. "I heard you didn't need qualifications, could make money fast, and dress up pretty while dancing," she said in an interview with Xinhua news agency. "It seemed like a way to live out my dream of being a star."

Instead, she found herself spending long hours not only dancing, but cultivating "relationships" with wealthy fans. "We repeat simple choreography all day and then maintain contact off-camera. The goal is to keep them spending."

In this world, tips aren't just money – they're currency for intimacy. Hosts study donors' profiles, mirror their hobbies, and offer "emotional value." Miss a sales target, and the host takes the blame. While companies claim to ban offline meetings, insiders say managers often encourage them if it means more cash. Boundaries blur quickly: late-night calls, private video chats, and sometimes far more.

Locked in and left out

Wage disputes are common. One performer told media outlet Beijing News she was reassured during her interview that a contract wasn't necessary. When payday came, the company argued that because nothing was signed, she'd be paid commission only. After 38 days of work, her paycheck totaled just 29 yuan (US$4.04).

Another host was slapped with a 200,000-yuan penalty for trying to quit early. She eventually paid 10,000 yuan just to escape.

"With filters on, anyone can be made to look perfect," one disillusioned performer was quoted as saying. "We're not stars. We're disposable."

According to a report cited by China Business Journal, China's online performance industry – including livestreaming and short videos – generated 212.64 billion yuan in revenue in 2024. Within that, the tuanbo sector alone is expected to grow into a 15-billion-yuan market.

In late July, Douyin, China's version of TikTok, tightened its rules on group livestreaming, rolling out stricter content and agency guidelines that target sexualized performances and tipping manipulation.

According to Xinhua, the platform has already expelled 54 guilds this year for violations ranging from spreading obscene content to offering brokerage services to minors.

The updated regulations ban contract traps and prohibit agencies from coaching or tolerating vulgar shows – moves the platform says are showing clear results.

Every evening after 6pm, around 15,000 streams lit up short-video platforms.

But for all the burnout, tuanbo continues to thrive. Its appeal lies not only in performance but in manufactured intimacy. Viewers aren't just tipping for choreography – they're buying connection, a sense of belonging in a virtual "idol group."

A handful of success stories still circulate, fueling hope among newcomers. But for most, the dream fades fast.

When asked by Xinhua whether tuanbo is worth trying, veterans give the same warning:

"If you have any other choice, don't do it."