When we talk of migrant workers, an image of lean but muscular men carrying bricks or binding steel bars on construction sites, rain or shine, comes to mind.

Fifty-eight-year-old Liu Shili fits perfectly into this image. A farmer from rural Henan Province, he has been doing odd jobs on construction sites in several cities, including Beijing, during non-peak agricultural seasons over the past three decades or so.

Like many other migrant workers, he usually gets up early in the morning and avails himself of local job markets in the hope of finding some temporary assignments on construction sites. But sometimes, no job turns up.

This is where he differs from his fellow workers. Hard pressed as he is to earn as much money as possible, he manages to find time to read books for free in a city's bookstores or libraries when no job is at hand.

In recent media interviews, Liu said he likes to visit bookstores or libraries where he can read various dictionaries, manuals on practical knowledge like welding and driving, and ancient Chinese poems. While practical knowledge helps him hone his skills as a competent worker, certain other books, including collections of poems, impart wisdom of life and help him better square up to challenges in reality.

"Reading brings grace to my life as a worker," he said.

Liu seldom buys books, though, because he moves around a lot, unable to carry books with him. On the other hand, he has to save every hard-earned penny for his rural family as well as for his basic living in a big city.

A respectable reader

Rarely did I realize that reading – part of my daily routine work – could be such a luxury for someone like Liu. To think that he cannot even afford to buy a book while every room of my suburban home in Shanghai is overstocked with books. Even my beds are spread with bedside reading materials.

Our pursuit of knowledge and wisdom is similar if not the same, but his perseverance commands more respect, because he has to travel a long distance on bumpy buses from a suburban labor market to a downtown bookstore, while a courier will deliver a book to my doorstep.

His silent and solitary search of knowledge and wisdom through constant reading would not have been known to the public had it not been for his chance encounter with Chen Xingjia, a well-known public welfare worker.

When Liu was browsing in a major bookstore in downtown Beijing on June 25, he noticed Chen's book-signing event taking place there. He had heard about Chen before, so he decided to go over and try his luck.

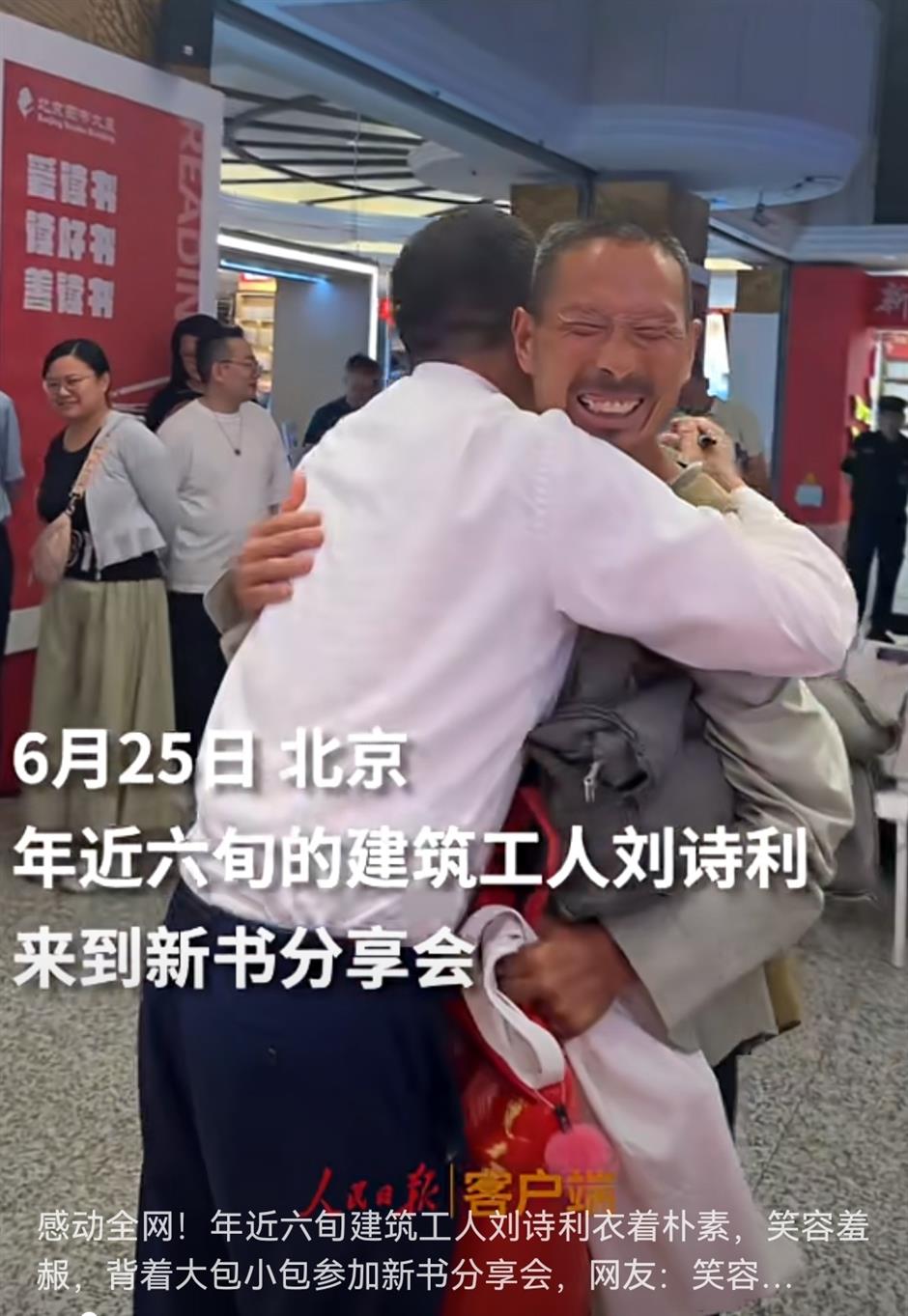

That day there were more than 100 readers waiting to get Chen's signed book published by People's Daily Press. Liu stood in a corner, his wrinkled face appearing a bit nervous. His image was so unique that he caught the attention of an editor from People's Daily Press who, having learned about Liu's background, decided to "cut the line" for him. Later, Chen gave his signed new book to Liu as a gift, and warmly hugged him.

Author Chen Xingjia (left) hugs farmer and migrant worker Liu Shili at the book-signing event.

The People's Daily Press editor shot a video of Liu's presence at Chen's book-signing event, which was then uploaded onto the Internet, generating nearly 50,000 comments. One netizen commented: "Why am I moved by Liu's story? Because he keeps reading despite all sorts of inconvenience, and because he pursues what he loves despite difficulties in life..." This comment alone generated 5,000 likes.

Simple style

Certainly, Liu's story is about a farmer who keeps reading to refresh himself despite having to toil and sweat hard in wheat fields in his hometown and on construction sites in faraway cities. But if we read Liu's article published in the People's Daily on July 11, we will know Liu has much more to teach us – that is, his simple, unassuming style of writing that reveals his genuine thoughts.

Here's my translation of the first paragraph of his published article, titled "Read to Make Ourselves Better."

"I'm Liu Shili. I come from Puyang, Henan Province. I plow the land at home during peak farming seasons. Otherwise I go and work in cities to earn some extra money. After harvesting wheat at home, I came to Beijing a few days ago and started to look for jobs in the Majuqiao area. One may find more job opportunities before 5am. It would be difficult to find a job after 7am. I do everything from binding steelbars and pouring concrete to building walls and screeding the floor. When there's no job, or after I get off work, I would visit the Beijing Book Building at Xidan and find something to read. I feel relaxed and happy each time I open a book. I can stay there seven to eight hours at one time. It feels good."

What a simple style of writing! No big words, no fancy concepts, no superlatives. Isn't this a better way of telling a story than resorting to sensational words that so often plague some social media outlets?

Liu is not the only farmer who can write a touching article with simple words. An Sanshan, a 66-year-old from Shanxi Province, has moved many people to tears with his 800-word improvised composition titled "My Mother."

On July 9, a vlogger went to a job market near the Taiyuan Railway Station and challenged some migrant workers to finish a 800-word composition. Anyone writing such a composition with a given title could win 1,000 yuan (US$138.66) as a reward.

An, who had waited five hours but got no job that day, decided to give it a try. As with a case of opening a "blind box," the topic he picked randomly happened to be "My Mother," the very composition title in the nation's college entrance exam in 1957.

An Sanshan picks up a composition topic from a "blind box."

An said he finished writing the composition in about an hour and a half. He wrote on a paper with a ballpen.

"The words flowed from my heart, " he said.

His article was dedicated to the memory of his mother, who died a long time ago. He remembered how hard his mother had worked for the family.

I attempt to translate the last paragraph of An's composition as follows:

"The grass on (my mother's) grave turns green, then yellow, then green again. Like my longing, it never fades. I've become a father, and a grandfather, but for more than 30 years I haven't called "mom." When I can no longer shoulder cement bags, I'll return to my village and lie down beside that small mound of earth. Then, if I call 'mom' again, she may hear me."

These are the simple words that have moved myriad netizens to tears. As a reporter, I have a lot to learn from this reverend farmer, whose words simply follow his heart and truly reflect a beautiful mind that no fancy words can describe.