Kate Wenqi Zhu's second-place finish in this year's Leslie Fox Prize in Numerical Analysis, organized biennially by the UK's Institute of Mathematics and its Applications (IMA), was more than a personal triumph.

The prize is regarded as a highly renowned international honor for young researchers in numerical analysis, recognizing exceptional talent among individuals under 31 years of age.

Zhu was one of six finalists selected from a large pool of submissions – Oxford's only finalist and the only Chinese winner at this year's awards.

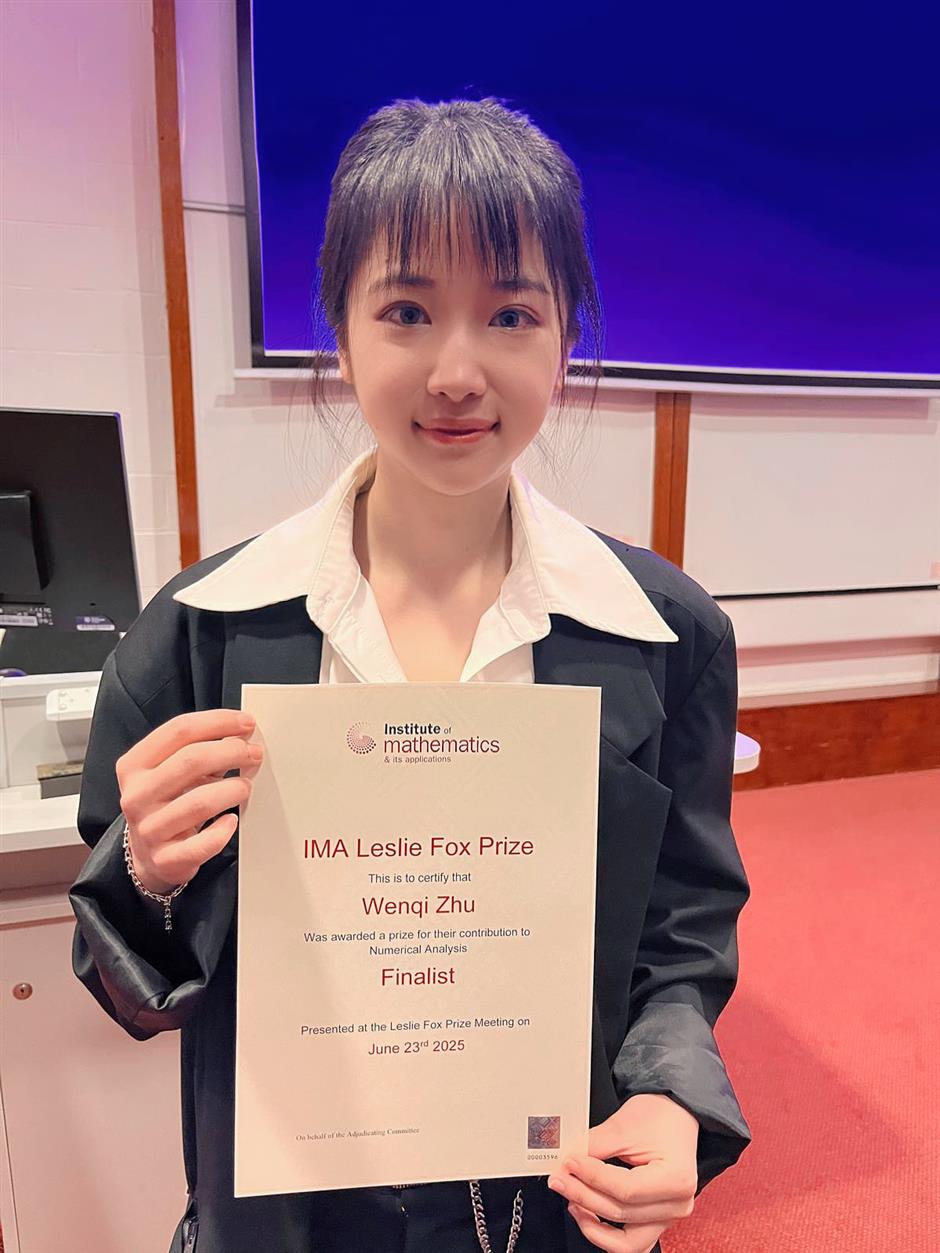

Kate Wenqi Zhu won the second prize at the IMA Leslie Fox Prize in Numerical Analysis.

It all began on January 30, Zhu's 31st birthday, despite her belief that she hadn't gathered enough experience as a PhD student, she gave it a try. In March, the invitation arrived: she had been selected to present.

"I've never felt nervous for most exams or stage presentations," Zhu said. "But this time was different – it was my last chance."

Yet, when the presentation finally ended, Zhu felt calm and relieved. "Because I had done everything I could. As mathematicians, we need to know what's within our control and what isn't. We do our best, but the outcome is up to fate."

Kate Wenqi Zhu was one of six finalists for this year's Leslie Fox Prize in Numerical Analysis.

Surviving online abuse

As news spread of the "Oxford top graduate wins international math prize," the story started trending in searches on Chinese media.

Zhu saw irony in this moment. Three years earlier, in 2022, the very phrase "Oxford's top graduate" had made her the target of online abuse.

Zhu posted a video on March 14, 2022, the International Day of Mathematics, announcing that she had graduated as the top student from the Mathematics Institute at the University of Oxford.

Her post has received over 1.2 billion views on Weibo, China's most popular social media platform.

Zhu's master's graduation photo from Oxford University.

Under the hashtag, there were no comments of congratulations – only widespread questioning and attacks accusing her of faking her certification.

Male influencers, including professors and representatives from education groups, scrutinized Zhu's daily posts, twisting her luxurious lifestyle and beautiful selfies into derogatory remarks, claiming she resembled a "cheap salesman."

The abuse ceased after Zhu solved a math problem posed by a male professor as a test to validate herself. "In that moment, I didn't see it as proving myself at all. I chose to do it because I respect math. I knew I could solve it, so I did."

The incident was not the first instance of her facing "compliance testing" imposed by men, as she did not conform to the stereotype of the "typical math genius." She was young, wealthy, and beautiful.

Zhu shares her daily life on the Chinese social media platform Weibo.

At 20, Zhu obtained her bachelor's in mathematics from Oxford in 2011. She then built a successful career in Hong Kong's finance sector, earning millions of yuan.

She often shared her delicate and elegant lifestyle on social media. "Most people think mathematicians only need simple food and a modest life. But I'm just a normal person. I love wealth, and I love math even more. I'm always trying to find a dynamic balance between building a fortune and pursuing what I purely love."

Zhu still posts her vlogs despite criticism and preconceptions. "I'm just showing a different way of living. I want more people to see that this kind of life is possible.

"I hope my experience can inspire others."

Expelled from school, learning at home

"My mom saved me," Zhu says.

Zhu endured bullying at her public primary school in Shenzhen and ultimately refused to attend until the head teacher expelled her.

In response, Zhu's mother, Zeng, quit her job and decided to homeschool her.

Although this decision proved to be wise, Zeng had no clear plan for her daughter's education; she took the risk out of anger at how the school had treated Zhu.

A childhood photo of Zhu.

Zeng herself was a bright physics student. She was one of six admitted to the School of the Gifted Young at the University of Science and Technology of China, a program designed for the nation's brightest minds. Zhu's father has a PhD in computer science.

Zhu's parents took a college-style approach to coach her on math and English. They wove mathematical theory into daily conversations and games, even turning dinner into a classroom.

"That's when I realized math wasn't just about solving questions. It's a useful tool in life," Zhu recalled.

In two years, her parents distilled six years of knowledge. Zhu got accepted to Shenzhen College of International Education at 12 despite not having a primary or middle school graduation.

Zhu entered a global world through that high school. "Through that door, I saw math, Oxford University, and the Leslie Fox Prize waiting for me."

At 15, the girl who was once considered the "bad kid" in primary school for scoring 45 on a math test became the youngest Chinese female student to study mathematics at Oxford University that year.

Math as a cure for depression

After the wave of online abuse, many still tried to shrink Zhu's achievements down to her background: the girl from a good family, with elite parents. But Zhu knew better. "Every mathematical proof, every piece of research, I did by myself," she said. "I do cry over cruel comments. I do feel angry. But I turned those voices into fuel to keep going."

Zhu has not received financial support from her family since the age of 19. If she wanted to stay at Oxford and pursue a master's degree, she had to earn it herself.

"My mom had gone through the struggles of academia, and she didn't want me to follow the same path. She hoped I'd find a well-paid, stable job in Hong Kong, which is close to her."

Zhu joined J.P. Morgan at 20 after her graduation, earning a million yuan yearly. But soon, a quiet emptiness set in. "I kept asking myself: Is this really the life I want?" she recalled. "I was deeply unhappy. Every day after work, I felt crushed. I'd go home and cry."

When she was diagnosed with depression, math became her anchor. "Whenever I felt like crying, I'd turn to math. If I solved one, I felt calm." The moment she realized math was what helped her heal, she resigned – even though her salary had already doubled – and returned to Oxford for her master's degree.

Zhu is currently doing a PhD at Oxford on a full scholarship, and this is the happiest period of her life. "I love writing; I love shaping ideas. If something wasn't good enough, I'm just going to rewrite it." And the eleventh idea she submitted to her supervisor won her the prize.

"I chose math back in high school, and I'm glad math didn't give up on me all these years."

Her Oxford life is meticulously planned. She sleeps only 5.5 hours per day. "I live like a high-efficiency machine," she said. "I'm incredibly busy, but everything runs smoothly – nothing falls apart."

Zhu at a cafe in Oxford in this 2022 photo.

Looking ahead

Zhu is working on advanced research in non-convex optimization, which is a complex and cutting-edge area of mathematics. Even though she has fulfilled the prerequisites for graduation, she has decided to stay in the course and improve her work.

She has written 10 manuscripts, two of which have been accepted by top mathematics journals, Mathematical Programming.

Zhu will begin a two-year postdoctoral study at Oxford when she receives her degree in November. Her yearly income is much lower in comparison to her previous work in finance. But, for her, that has never been the point.

"We should look further ahead," she said. "The goal isn't to make more money every year. What matters is who you will be in 30 or 50 years.

Zhu is also thinking about going home. "I am truly looking forward to returning to China," she said. "Whether it's academic research or public education in mathematics, I hope to give back to the field in my own country."