Hallett Edward Abend

In early 1926, a 40-year-old American journalist boarded the trans-Pacific liner Siberia Maru to explore the hitherto unexplored "New World" – China.

When the ship docked in Shanghai, Hallet Edward Abend (1884-1955) stepped into a rainy city, with streets marked by "shocking poverty."

What was supposed to be a brief excursion to the Far East turned into a 15-year reporting career that established Abend as one of the most influential foreign correspondents covering China.

By the time he left in 1940, Abend had written over 1,200 stories for The New York Times, many of them from the front lines of China's upheavals.

His scoops covered everything from the Northern Expedition in Guangzhou to the turmoil of the Jinan Incident, the January 28 Battle of Shanghai, and even the shocking details of the Xi'an Incident.

Abend described his years in China as "a series of adventures, extensive travel, and contact with men of every type who were making Asiatic history."

A frontline reporter

Abend's reputation was built on his willingness to go places others would not. Yang Zhifeng, who translated Abend's "Tortured China" into Chinese, characterized him as an individual who aspired to be the first to arrive at the scene.

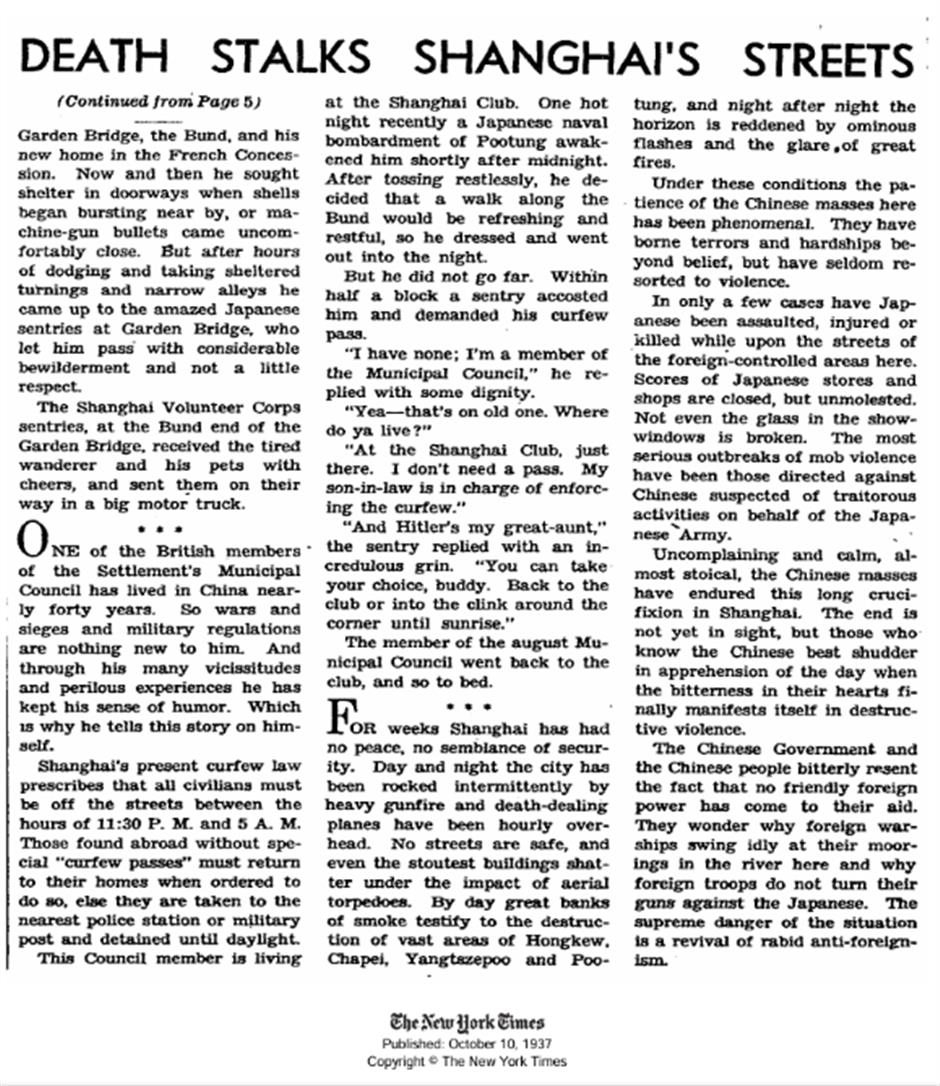

When the Battle of Shanghai broke out in 1937, Abend rented a room barely eight streets from the North Station bombing zone. He was typing when shrapnel hit the walls of his balcony. On October 10, 1937, he published an article headlined "Death Stalks Shanghai's Streets."

"For weeks, Shanghai has had no peace, no semblance of security. Day and night, the city has been rocked intermittently by heavy gunfire, and death-dealing planes have been hourly overhead."

Abend not only recorded battlefield conditions, but it also introduced Western readers to major individuals in Chinese politics, including Soong Mei-ling, Soong Tse-vung, Chang Hsueh-liang, Soviet advisor Mikhail Borodin, and Japanese commander Hashimoto Kingoro.

When Hu Shih was imprisoned in 1929, Abend wrote a scathing editorial decrying the Nationalist government's persecution of "a philosopher, distinguished, courageous, frank in thought and speech." The widely distributed article played a crucial role in securing Hu's release.

His reporting also highlighted Japanese crimes. Abend reported in February 1938 that General Iwane Matsui, commander of Japanese forces in Central China, made "an unprecedented admission of serious indiscipline in certain contingents of the Japanese Army operating in the Yangtze Valley" – a veiled reference to the Nanjing Massacre.

The reluctant insider

Despite government pressure, Abend maintained his neutrality. During the Jinan Incident, he took notes from a refugee-packed train, determined to provide an "absolutely impartial account" of the eight-day conflict. That commitment frequently enraged Chinese authorities, who attempted to remove him several times.

Abend remained vital to the exchange of information between China and the West. His front-page Times series on the Xi'an Incident ran for 15 straight days, which was unusual even at the time.

He dubbed his China expedition the "second rebellion." The first occurred when he left the media for a futile experiment in the backwoods of British Columbia, attempting to subsist as a dramatist and novelist.

In 1905, he dropped out of Stanford University and began reporting for The Spokesman-Review in Spokane, Washington, for US$10 a week.

Abend was never satisfied in the office, despite rising through the editorial ranks and eventually becoming editor-in-chief. "I considered the China story as my egg," he later wrote. "I was determined to sit on it until it hatched."

When American media refused to send a correspondent to the Far East, Abend paid for his trip in 1926. Shortly after his arrival, he found himself under siege on Guangzhou's Shamian Island amid revolutionary turmoil, a risk that would come to define his career.

Witness to Shanghai's transformation

After being exiled from Nanjing in 1929, Abend was reassigned to Shanghai, where he worked as The New York Times' main China reporter until 1940. From his Bund office, he hired and oversaw correspondents from throughout the country.

He documented Shanghai's evolution into a global metropolis, from department stores "owned and successfully operated by Chinese" to silver shops where "the art of silversmithing is an ancient one in China, and silver shops are filled with many objects of beauty and utility distinctive of the country."

The Japanese flagship Izumo, a frequent target of Chinese attacks, anchored on the Huangpu River during the Battle of Shanghai. Published on October 8, 1937, in The New York Times.

He described Suzhou Creek as "one of the busiest waterways in the world," with boats transporting everything "from watermelons to pig iron and from brick to flour."

His dispatches from Shanghai, however, focused on the metropolis under assault. Reporting on the 1932 battle, he called the Japanese bombing of unarmed civilians "the most cruel massacre, which enraged all humanity." He also noticed the resilience of regular Shanghai residents, who remained "almost stoical, calm, almost self-denying, bearing suffering for so long."

Abend's years in China coincided with a watershed moment: the buildup to the US-China wartime alliance. Though he is scarcely known today, his time as one of The New York Times' early correspondents in China left a lasting impression.

He shaped how the West perceived China's revolutions, conflicts and societal transformations throughout the 15 years. His dispatches provided readers, ranging from the general public to members of Congress, with a vivid portrait of a country in turmoil and transition.

Abend may have referred to himself as a witness, but he was much more: a chronicler whose steadfast impartiality, taste for danger, and keen eye ensured that China's story reached the world.

(The author is a second-year graduate student with Journalism School, Fudan University.)