Peter Corne, an Australian by birth and a Shanghainese by status, is a peacemaker in the world of commerce.

He handles business-related cases for both the Shanghai Commercial Mediation Center and the Shanghai International Arbitration Center. Both centers mark an important step in the modernization of the city’s legal framework.

Corne is managing director of Dorsey & Whitney LLP’s Shanghai office and co-chairs the international law firm’s US-China Practice Group and Clean Technology Practice Group, at the same time holding down a position as Shanghai chair of the Environmental Working Group of the European-China Chamber of Commerce.

In 2017, he received the prestigious Magnolia Silver Award for his contributions to the city, primarily in dispute resolution in the China (Shanghai) Pilot Free Trade Zone.

“Peter is a true pioneer in dispute resolution, anti-trust, clean energy and sustainability fields in Shanghai, and in China generally,” Ken Cutler, Dorsey & Whitney’s then managing partner, said at the time. “He is committed to making Shanghai a truly international hub.”

As a go-between in mediated disputes, Corne works with both sides to find acceptable solutions. He is a specialist in the mediation of international transactions, cross-border disputes, environmental and clean technology issues, and regulatory and compliance issues.

Peter Corne plays host at the launch ceremony of a co-mediation mechanism on intellectual property established by the Shanghai Commercial Mediation Center and the Boards of Appeal of the European Union Intellectual Property Office.

Most recently, he was involved in helping draft new rules on mediation disputes involving the European Union and China on issues related to technology transfer, patents, trademarks and designs. The co-mediation rules governing the management of such disputes came into effect earlier this month.

He has studied legal systems in both China and Japan, and speaks the languages of both countries fluently. He was an exchange student at Renmin University in Beijing, where he met his future wife and married in 1990. After the scholarship ended, he returned to Australia to work as a lawyer. In 1994, he moved to Hong Kong to work for a British law firm.

“At that time, lots of foreign firms were applying for licenses to open offices in China,” he said. “Some of them managed to get their license in Shanghai. So my firm sent me from Hong Kong to Shanghai.”

He added, “I had the opportunity to come and work in the city in 1996. I didn’t really choose the city in which to settle down; I think the city chose me.”

Here, he developed a particular interest in mediation and arbitration.

“I always loved mediation,” he said. “I was trained in mediation at quite an early stage in my legal studies in Australia in the 1980s. But when I came to China, there wasn’t much opportunity to do international commercial mediation, so I was really waiting for the opportunity. I found it when the Shanghai Commercial Mediation Center opened and invited me to join eight years ago.”

The center, he said, sits at the forefront of mediation in China because of its high professionalism.

“All the mediators are quite high-level and there are many who have good cross-cultural and bilingual skills,” Corne said. “That allows us to understand what’s going on underneath a business dispute and use our cultural skills to engage the disputants to get them to disclose their real concerns.”

Corne explained the distinction between mediation and arbitration. In the former, a mediator works with both sides trying to reach an agreement. In arbitration, which is like a private court, an arbitrator listens to arguments from both sides and arrives at a decision as to which party to the dispute has the stronger case.

Peter Corne displays the certificate authorizing him as an arbitrator at the Shenzhen Court of International Arbitration.

Corne said he prefers mediation because the parties involved are in control of the process and can be more creative. Instead of there being a winner and loser in the outcome, an amicable mediation settlement often means both sides will continue their business relationship.

“The fact that they’ve agreed to mediation is a good sign, but it doesn’t mean that they see things in the same way,” he said. “That’s the job of the mediator, to try and manipulate the process to get the disputants to understand the other’s perspective.”

Then, too, mediation is usually faster and cheaper than arbitration or a court case.

“Arbitration, the main form of dispute resolution between companies in different countries, can be quite expensive,” Corne said. “A lot of companies don’t want to spend that amount of time or money on a dispute. Mediation is great for small and medium-sized enterprises.”

Corne helped resolve the first mediation case between two foreign parties in the free trade zone. In that case, the plaintiff was a foreign individual who had signed an equity-transfer agreement with an overseas company. It required payment within 10 working days of the transfer. But the company didn’t make the payment on time.

After some negotiation, the payment period was extended, but the payment promised by company wasn’t forthcoming. The plaintiff then took the company to the Pudong New Area People’s Court.

The center then dispatched Corne to mediate this dispute. He first eased the antagonism between the two sides and then asked them to lay out their arguments. The company, it turned out, was in some financial trouble. Corne finally got both sides to agree to phased payments over six months.

The case was seen as landmark in the development of the zone, which is home to many foreign firms and individual businesses and seeks to be a leader in modern global commerce.

In his role as chief arbitrator, he also assisted in the first foreign trade dispute that went to the Shanghai International Arbitration Center from the free trade zone.

It involved a contract dispute related to gas supply between a foreign-invested company and a domestic enterprise. The agreement they signed required arbitration of any disputes be conducted in English, with a foreign arbitrator.

Corne said he has watched with satisfaction the development of mediation and arbitration services in Shanghai. In the beginning, there were difficulties, including immature processes and linguistic and cross-cultural challenges in business practices.

“We didn’t really have any true commercial mediation back then,” he said. “When there were disputes, businesses sometimes reverted to arbitration centers overseas, which could be very expensive.”

He added, “Shanghai has been very proactive in trying to improve its regulatory environment, and part of that is the dispute-resolution system. The city very much wants to become an international dispute-resolution center. I really want to make that happen, particularly in the free trade zone.”

The city will be setting up more international arbitration centers in other areas, such as the Lingang New Area, which was recently added to the free trade zone.

“That’s an exciting development,” Corne said. “It will further internationalize the industry, ushering in higher standards. It’s only the beginning.”

(Kiera Yu also contributed to the story.)

Mediators help bridge gaps when there’s disagreement

Besides Corne and his five foreign colleagues at the Shanghai Commercial Mediation Center, there are more foreign mediators working with local judicial offices or legal organizations by dealing with civil disputes, mainly those involving foreigners.

In Changning District, a dispute resolution system has been set up for civil affairs for years with foreign volunteers acting as mediators.

The Hongqiao Office of Changning District Bureau of Justice encouraged legal advisers of communities where some expats are living to look for foreign residents who can understand Chinese and are familiar with Chinese culture. They were then invited to be the justice office’s voluntary mediators.

These foreign volunteers also helped with the communities’ law promotion and collecting foreign residents’ advice on the practice of policies in communities.

The justice office also connected the local branch of Japanese law firm TMI Associates and ForNGO, a non-profit organization specialized in law research to provide training courses about foreign-related mediation.

In one case, an Australian man unintentionally scratched a Chinese resident’s vehicle when he was parking his car.

The traffic police thought the Australian should take full responsibility in this incident.

But due to the language barrier, the two sides had a dispute on compensation and failed to reach an agreement. The Australian admitted fault but said the required compensation was too high.

He said if the same incident happened in his home country, the compensation would be far less than he was charged.

He refused to receive mediation and told the car owner to bring him to court or turn to the embassy.

Faced with apparent deadlock, the justice office entrusted ForNGO to send a foreign mediator to interfere into this case.

A Japanese mediator with the TMI Associates law firm mediates in a dispute involving foreigners and residents at a hearing at the Gubei Civic Center.

An Australian mediator with ForNGO offers his advice in a dispute.

A Chinese-Australian mediator contacted the man and explained that they didn’t mean to force him to accept mediation. Since this issue is quite small, they hope the two sides can find a solution and mediation is a good choice.

With her efforts, the Australian man finally agreed to have mediation with the car owner Jiang.

Meanwhile, Lin, a lawyer with ForNGO who studied overseas, approached Jiang and sought to lower the amount of compensation he demanded.

The case ended with the Australian’s paying Jiang more than 2,500 yuan (US$359) to repair the car.

In the district’s Ronghua residential complex, there are some 32,000 residents and more than half of them are expats from 50-plus countries and regions.

Given the name “Mini United Nations,” this complex provides various services to meet the residents’ needs.

The foreign volunteers have fully participated in the communities’ daily routines and matters in connection with residents’ concerns, while the Chinese community workers are trained in foreign languages.

The volunteers are also invited to attend discussions and mediation over issues such as housing rents, parking or floor leaks.

Online platforms and offline salons are also provided for foreigners to keep up with the latest regulations and policies.

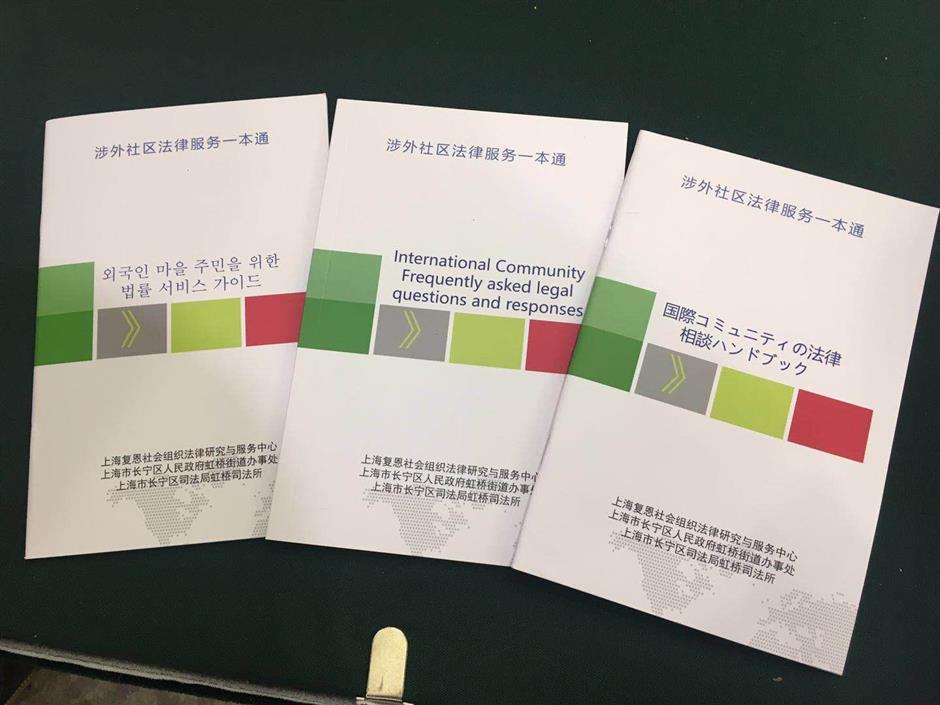

A Q&A brochure on legal services for the international community in four languages — Chinese, English, Japanese and Korean — has been released by the Hongqiao Office of Changning District Bureau of Justice, ForNGO and Hongqiao subdistrict with the assistance of foreign volunteers.