China's Art Market Surges on New Capital and Shifting Tastes, But Lacks Critical Foundation

China's art market is currently thriving, yet it stands on uncertain ground. Chinese collectors, flush with capital and confidence, are driving a global trend: high-net-worth individuals now dedicate approximately 20 percent of their wealth to art. Notably, women in China are spending twice as much as men, and the nation's domestic art outlays lead the world.

This surge in spending was recently confirmed by the UBS Survey of Global Collecting 2025, which tracks spending across fine art, decorative art, and antiques. Released just as the 7th edition of Art Shanghai wrapped up simultaneously at the West Bund and the Shanghai Exhibition Center early this week, the report showed that Chinese collectors remain the world's biggest art spenders, allocating an average of US$2.2 million a year to art and antiques.

Yet, beneath this vigorous activity lies a fragile foundation: pricing still lacks clear benchmarks, institutional depth is thin, and the country's collecting culture for contemporary art has yet to mature into a legacy.

Behind the art fair's packed halls and polished presentations, dealers described a market still defined by concentration: strong activity at the top, but limited depth beneath. This unevenness is less a sign of weakness and more an indication of a maturing phase: the market possesses the capital, but its infrastructure for value discovery is still catching up.

"Contemporary art in China never underwent the organic evolution seen in the West, nor does it possess the deep cultural and aesthetic consensus that underlies traditional Chinese art or antique collecting," said Jia Li, an independent art advisor and Shanghai-based critic. Jia, who formerly worked with major galleries, now consults directly with private clients.

"It didn't grow from a philosophical or institutional base," she elaborated. "It arrived as a format, imported alongside capital and global recognition." She said that, without a mature museum system or critical discourse to properly frame artistic value, collecting has developed faster than understanding.

"People here buy contemporary art," she added, "but the concept of why it matters – socially, historically, and intellectually – is still forming."

UBS, however, takes a broader view. Its survey encompasses not only contemporary art but also fine art, decorative works, and antiques – sectors that rely on vastly different systems of legitimacy and value. While traditional and antique collecting in China has long benefitted from cultural recognition and stable valuation frameworks, contemporary art remains a field where meaning and market still move at different speeds.

Jia pointed to scenes from this year's West Bund fair, where some mid-career Chinese artists were asking several hundred thousand yuan for abstract works comparable in scale and quality to those priced under 70,000 yuan (US$9,754) in Europe. "That gap speaks less to confidence than to calibration," she said. "The market here often moves ahead of its critical foundations, and prices are still testing where real value lies."

Adding to this complexity is a generational shift reshaping China's collecting landscape. Younger buyers, many of them entrepreneurs or professionals in tech and finance, approach art less as an asset class and more as an element of lifestyle. Their focus is on personal taste and identity, rather than cultural belonging or traditional connoisseurship.

This appetite for immediacy among younger collectors has significantly expanded what counts as "collecting." Decorative art, design furniture, and limited-edition objects are now entering the same conversation as traditional paintings and sculpture. According to the UBS report, this trend aligns with a broader global movement: millennials and Gen Z collectors are more likely to cross categories, seamlessly blending fine art with digital and experiential forms.

"For Gen Z and Millennial collectors, art is not confined to traditional mediums," said Eric Landolt, Global Co-Head of the Family Advisory, Art & Collecting department at UBS.

"They are buying across categories, such as designs, digital works, and collectibles, which points to a more fluid and globally minded understanding of culture today," he added. "We are observing that galleries and art fairs are looking to adapt by diversifying their offerings and creating spaces that celebrate this cross-category collecting."

That generational shift was also prominently displayed at this year's West Bund art fair. Many galleries appeared to be tuning their language toward younger buyers, presenting works that were more decorative, chromatically bold, and instantly legible. This included paintings with glossy surfaces, playful figuration, or cartoon-like elements that photograph well and fit easily into domestic interiors.

This shift reflects a pragmatic reading of the market: collectors in their twenties and thirties are shaping the next phase of demand, even if their motivations differ from those of their parents. Yet, as independent critic Jia observed, this trend also highlights a generational disconnection.

"Many second-generation collectors have little emotional link to the contemporary art their parents championed," she said. "Those big-name works command high prices today, but no one can say if they'll carry the same relevance, or value, in 20 or 30 years."

She added that she has heard many younger heirs tell their parents outright, "We don't want these collections in the future."

While younger collectors are broadening the market's visual language, women are quietly redefining its tone. Their growing presence adds a different kind of stability – one that is slower, more deliberate, and often more attuned to narrative than novelty.

"They tend to take more risks in supporting newly discovered talent," said Landolt. "Their approach is often more passion-driven, motivated by engagement and curiosity rather than investment calculus."

The art report reveals that women's average spending on art and antiques was 46 percent higher than men. In Chinese mainland, high-net-worth female collectors led the expenditure, averaging more than twice that of men. Furthermore, female high-net-worth collections included a higher share of works by female artists and demonstrated a greater openness to newly discovered talent.

But not everyone agrees with that picture. "In China's contemporary art market, ultra-high-net-worth collectors are still overwhelmingly male," said the critic Jia. "It's true that younger women are more visible; they show up, they buy, they shape taste, but that doesn't mean they dominate the field."

But she also admitted this new wave of female collectors has already shifted market aesthetics. "A decade ago, the auction stars were all men, artists with grand, masculine narratives. Today, the rising names like Xia Yu, Wang Yifan or Ji Xin are those whose sensibilities resonate with female collectors. These aren't just trends; they reflect who has the purchasing power now," she said.

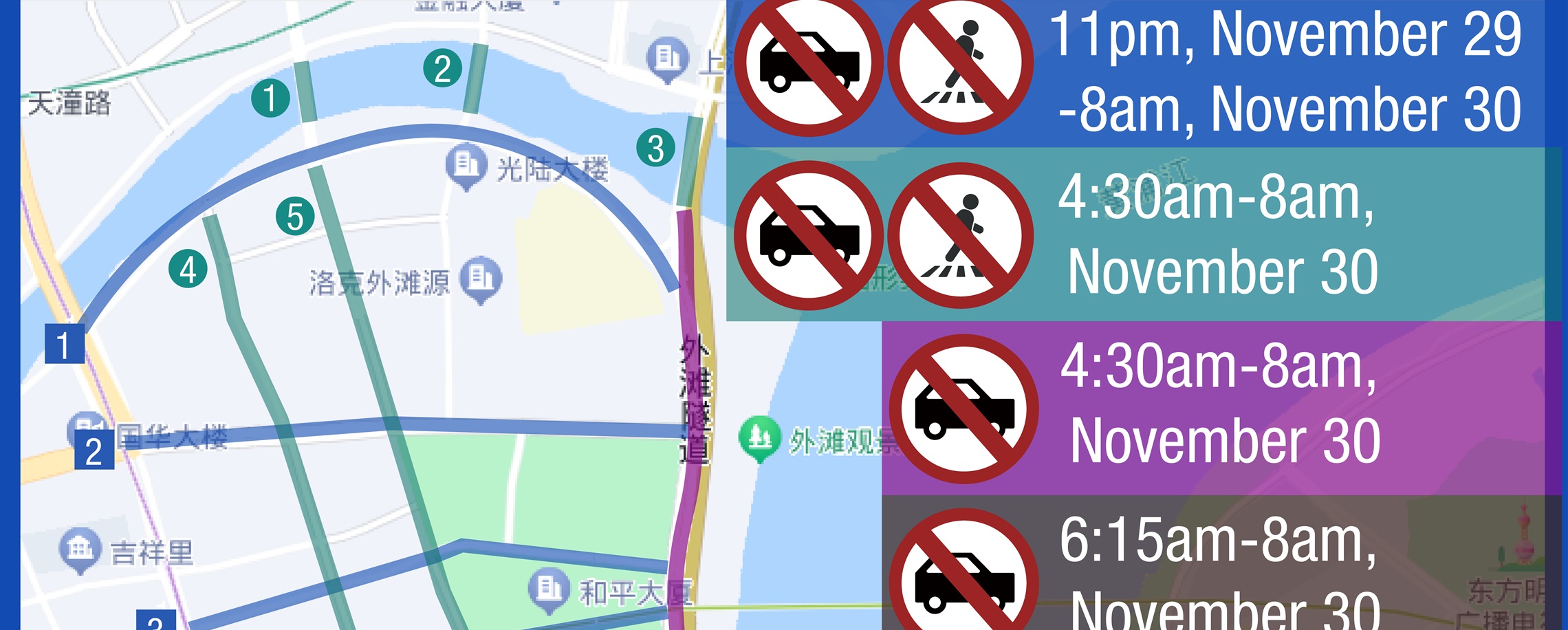

In Case You Missed It...