Spinning fragility into works of art that endure

A colossal sphere of cotton thread looms at the entrance – 2.5 meters across, dense yet fragile. Every strand was wound by hand, circling endlessly until the everyday act of wrapping became a monument to time itself.

Next to it, an embroidery hoop bears a single line stitched in pale thread: There's No Fun in It!

When Lin Tianmiao, 64, first made this work in 1997, it sounded like a throwaway joke, part shrug, part confession. Today, it stands as a declaration of intent, lending its name to the artist's largest retrospective at Shanghai's Power Station of Art.

For three decades, Lin has transformed humble materials – such as cotton, hair, and household tools – into works that are both intimate and monumental. Through the tactile experience of thread between her fingers, she has spun a visual language that addresses themes of exhaustion, absurdity, and the fragile resilience of the human body.

This exhibition, curated by Pi Li, showcases over 40 pieces that trace her artistic journey from the 1990s to the present, revealing an artist who finds meaning not in spectacle but in perseverance.

"The body's feeling is the most reliable," Lin said. "Pain, repetition, even waste – these are not failures. They are where new meaning begins."

Like the Greek myth of Sisyphus, condemned to roll a stone up the mountain only to watch it tumble down, this giant cotton ball embodies the futility – and the strange dignity – of repetition. The labor is excessive, almost absurd, yet it transforms the smallest gestures into a form of endurance. What seems meaningless becomes a way to insist, to persist, and to keep creating in the face of exhaustion.

If the cotton sphere is her Sisyphus stone, then the thread becomes her weapon and her wound. In "Bound and Unbound" (1997), everyday objects – chairs, tools, books – are smothered under tight skeins of white thread, stripped of function until they hover between relic and ghost.

Across the room, "Braiding" (1998) shows a monumental self-portrait of the artist punctured by thousands of threads, the strands cascading into a single heavy plait. On video, hands braid and unbraid endlessly, the gesture repeated until it erases itself.

"These gestures came from pressure," Lin recalled. "At that time, I had just become a mother. I felt surrounded by family roles, by expectations, and by the simple fact of being a woman and an artist. Wrapping, repeating, braiding – it was the only way to make that absurdity visible."

What might appear delicate is, in fact, grueling. Each thread is a record of hours, numb fingers, and labor stretched to the point of waste. Yet within that waste lies defiance.

As curator Pi Li explained, the art scene of the 1990s was full of irony and playfulness. Lin chose a harder path. "Instead of jokes or slogans, she used enormous, almost impossible amounts of labor to show what could not be spoken," he said.

To bind until an object disappears, to braid until identity frays – these are not acts of despair but of persistence. In the thread, Lin makes visible what life tries to conceal: exhaustion, absurdity, and the fragile strength that comes from doing it anyway.

From the thread, Lin moved closer to the body itself. Works like "Skin" (2005) enlarge pores and hairs onto silk, turning them into garments that seem to wear the body rather than cover it.

In "Loss and Gain" (2014), bones and tools are fused into strange hybrids: a femur grafted to a hammer, a spine stretching into a shovel. Spread along the wall like a skeletal orchestra, they speak not of function but of its collapse. The work is not about death itself, but about what remains when the body's framework loses purpose.

"The body's feeling doesn't lie," Lin said. "Pain, aging, even weakness – those are truths I trust more than anything else."

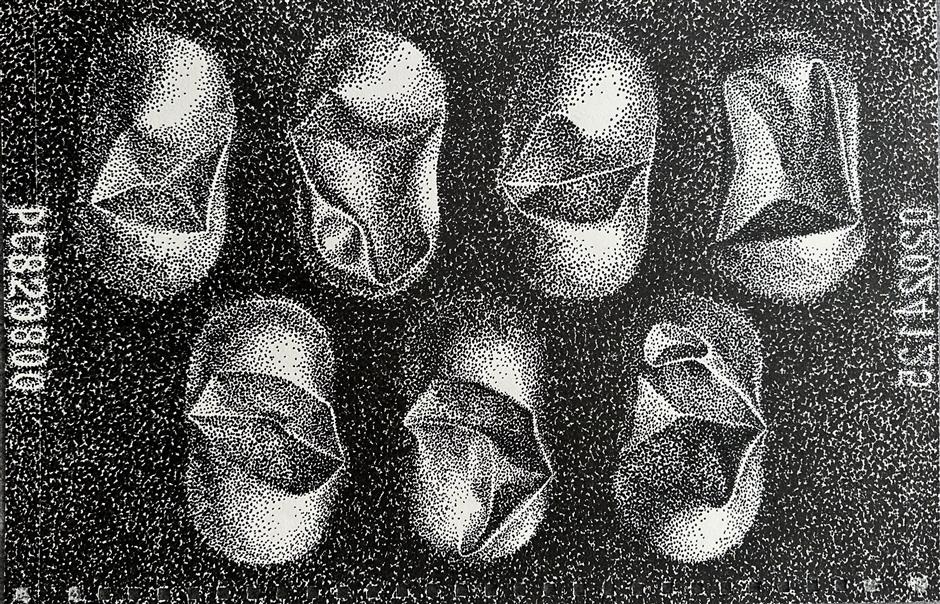

Her art does not present the polished surfaces of an ideal body; it confronts the marks of living, the texture of vulnerability. Years later, during a period of illness, Lin spent up to 12 hours a day tethered to IV drips. She began to watch the liquid fall, drop by drop, noting how each one caught the light.

"Every day I lay there, staring at the drip," she recalled. "Some were clear, some faintly red, and after a while, I thought, why not respond with the simplest gesture? So each time a drop fell, I marked a dot on paper. It became a kind of dialogue with myself – both an escape and a form of healing."

The resulting series, "Each Drop, Each Dot" (2021-2022), transforms passive waiting into a quiet act of endurance. What might seem monotonous – one dot after another – becomes a constellation of persistence, a record of survival inscribed through time and the body.

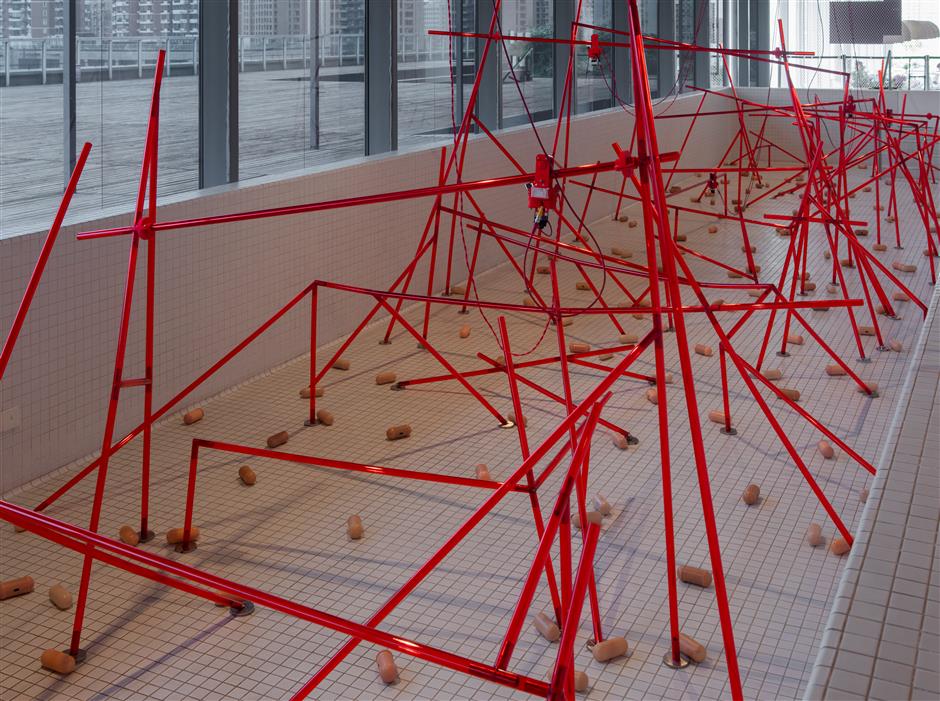

The most recent work, "Little People's Kingdom" (2024), spreads across a cavernous hall like a living organism. Dozens of small humanoid machines shuffle and collide, their motions projected live onto the surrounding walls.

The space feels both intimate and overwhelming: red tubes snake across the floor like exposed veins, while mounds of discarded pill foils glint under the lights, as if the room itself were a body under stress.

What emerges is a restless, fragile system – half city, half anatomy – where control and chaos coexist. The viewer is caught inside a body that could just as easily be a metropolis, its pulse driven by endless circuits of consumption and survival.

"It's not a playground," Lin said. "Those little machines, the red tubes, the mountains of pill foils–they create a space that feels both like a body and a city. You sense pressure, even loss of control, and that's exactly the point. I want people to confront how fragile the relationship is between the body and the world it lives in."

Date: through January 4, 2026

Venue: Power Station of Art 上海当代艺术博物馆

Address: 678 Miaojing Rd 苗江路678号

Admission: free