Shanghai under siege: A US missionary's forgotten chronicle of 1937

The windows shook with every distant explosion on September 4 1937. Clifford W. Petitt sat hunched over his typewriter in an office at the Foreign YMCA building on Shanghai's Nanjing Road, listening to the eerie whistle of artillery fire.

The American missionary had lived in China for nearly two decades, but this was unlike anything he had ever seen.

Bombs fell close enough to rattle glass panes, and the once-bustling racecourse outside was cloaked in smoke.

"The explosions made us shrug our shoulders," Petitt typed in his letters to friends in the United States.

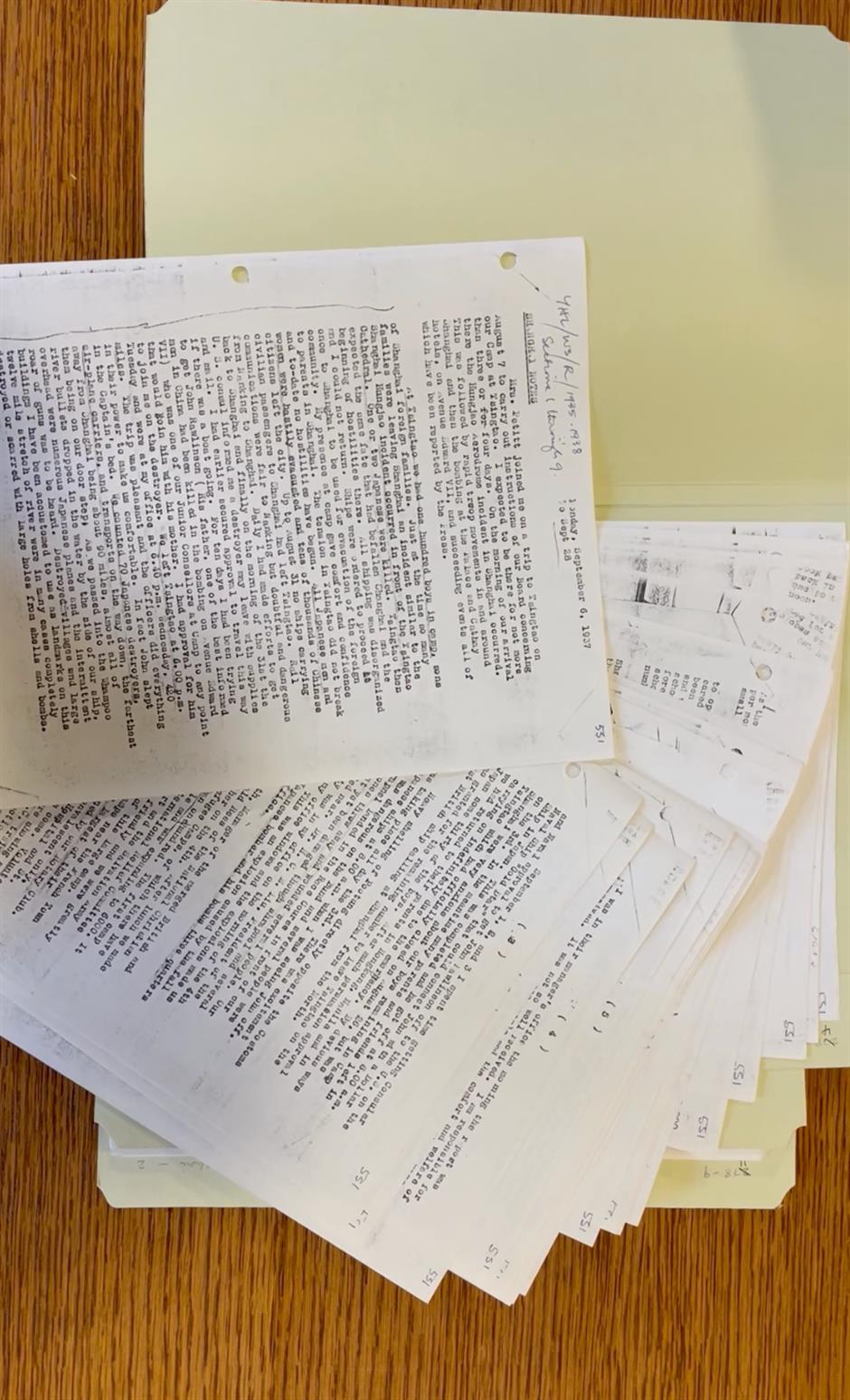

By December, his Shanghai Notes – a nine-part, 25,000-word chronicle – had become one of the most detailed eyewitness accounts of the Battle of Shanghai, a brutal early chapter of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.

His words capture a city under siege: soldiers digging trenches beside tramlines, refugees flooding the International Settlement, and the defiant heroism of Chinese troops at the famous Sihang Warehouse.

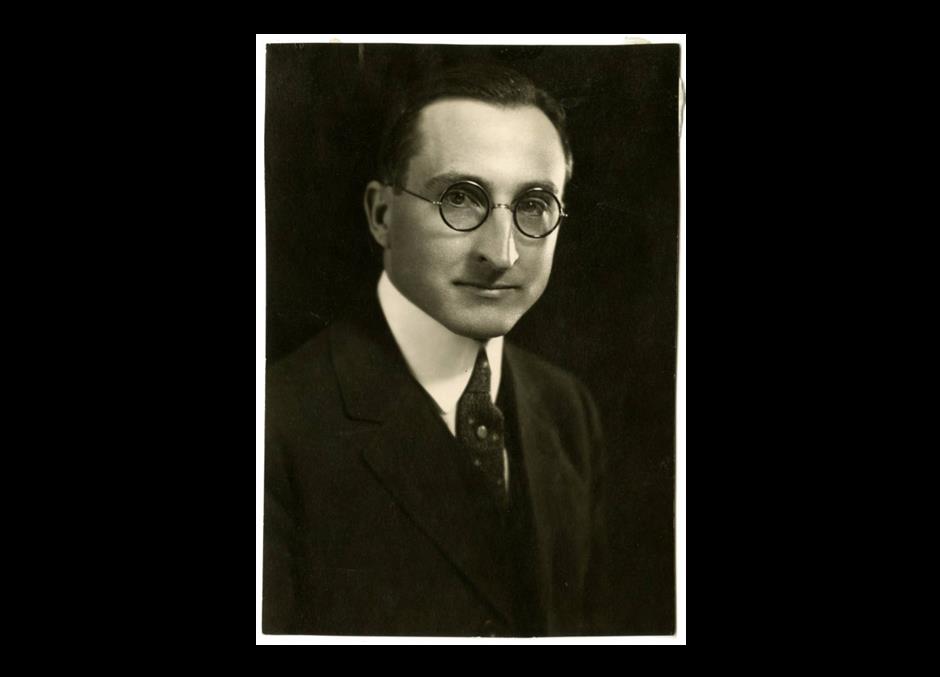

Clifford W. Petitt: Missionary, Teacher, Witness

Born in 1890 on a Kansas farm, Clifford W. Petitt first came to China in 1918 to study Mandarin in Beijing. By 1936, he was working in Shanghai as a YMCA administrator, overseeing education, sports, and community outreach programs.

Fluent in Chinese, he cultivated friendships across Shanghai's diverse communities and served as a bridge between expatriates and locals.

When war broke out, he could have fled. Instead, he stayed to help evacuate Western families while documenting the siege unfolding around him.

In the summer of 1937, Shanghai was China's cosmopolitan jewel. Jazz spilled from dance halls, neon signs glowed over the Bund, and department stores rivaled those of New York and Paris.

But the city's glittering façade masked deep political tensions. On August 13, after escalating skirmishes, Japanese and Chinese forces clashed in what would become the months-long Battle of Shanghai.

Within days, the city was transformed. On September 3, Petitt witnessed bombs fall on the horse-racing grounds near the YMCA building, injuring civilians and scattering debris into the streets.

The next morning, a Japanese bomber caused destruction "three quarters of a mile north of" his office.

The Battle of Shanghai was a turning point in world history. For over three months, Chinese forces, vastly outgunned and outnumbered, mounted a heroic defense in one of the largest urban battles of the 20th century.

The YMCA building became a vantage point for Petitt's observations. He witnessed the defense of the Sihang Warehouse, where a few hundred soldiers held their ground for days within sight of the foreign concessions.

"For three days and nights this 'suicide battalion' has refused to leave ... For those days from the rear windows of our building we could see those men and the Japanese shooting at each other the edges of the roofs," he wrote.

Petitt described the battle in detail, noting that some Japanese shells overshot the Chinese positions and landed near the Bund. He watched as exhausted Chinese soldiers retreated through the racecourse outside the YMCA, saluting their courage in his notes:

"They did a spectacular thing. They focused world attention on the heroism of China's army. They annoyed the invaders beyond words to describe."

By November, Shanghai's defenders were forced to withdraw, and Japanese forces took control of the city's Chinese-administered districts. The devastation was staggering: more than 250,000 people were killed or wounded, and vast sections of the city lay in ruins.

The international settlement: a fragile haven

While Chinese neighborhoods bore the brunt of the bombing, the foreign-controlled International Settlement offered a fragile sense of security. Petitt described sandbagged embassies, soldiers stationed at intersections, and expatriates debating whether to evacuate or stay.

Shops remained open, though their windows were crisscrossed with tape to keep glass from shattering. Cafés still served coffee, even as patrons flinched at the sound of distant gunfire. Foreign journalists, missionaries, and businessmen lived in what Petitt called "a curious blend of war and normalcy," where parties continued in the evenings, but curfews loomed.

The Settlement's apparent safety attracted thousands of refugees, many of whom had lost everything. Petitt recorded the sight of families sleeping in doorways, mothers nursing infants on street corners, and makeshift soup kitchens springing up in church courtyards.

A Testament to Shanghai's resilience

One of the most striking contrasts in Petitt's account is the persistence of leisure and culture amid destruction. Even during the height of the battle, the YMCA hosted sports events to boost morale. Basketball tournaments and tennis matches were organized, often featuring both Chinese and expatriate teams.

As Christmas approached in 1937, the YMCA hosted celebrations for 1,500 children–1,000 Chinese and 500 foreign – providing each Chinese child with a winter coat. Petitt viewed these events as small acts of defiance, proof that community spirit could endure even in wartime.

During World War II, the YMCA building was seized and renamed the East Asia Athletic Association. After Japan's surrender in 1945, it became a US military club.

In 1950, the new Shanghai government repurposed it as a sports center. In later decades, it hosted Olympic champions like swimmer Yang Wenyi, and Chairman Mao himself reportedly swam in its pool. Today, it houses the Shanghai Sports Bureau and a museum, welcoming visitors from around the world.

In 1945, after eight years of brutal warfare, China celebrated its victory over fascism. Petitt returned to the United States in 1939. The Shanghai he had known had been forever changed.

Yet his words endure as a reminder of Shanghai's resilience.

As China commemorates the end of the Second World War, Petitt's Shanghai Notes serves as a powerful artifact of memory. It is a testament to the city's endurance and to those who risked everything to bear witness.

Today, thousands of shoppers stream past the intersection of Nanjing Road West and Huanghe Road, where the YMCA building still stands. Few stop to imagine its dramatic past.

Standing before its art deco façade, you can still trace the outlines of history. Inside, the Shanghai Sports Museum tells stories of champions and milestones, but its walls also echo the rattling windows of 1937 and the courage of those who endured.

In Case You Missed It...

![[China Tech] BCI-Assisted Ultrasound Used to Treat Brain Disease](https://obj.shine.cn/files/2026/01/30/736cac37-b592-495f-b4e9-bbd0d1e34aad_0.jpg)