Can Collectible Design Become a Real Market in China?

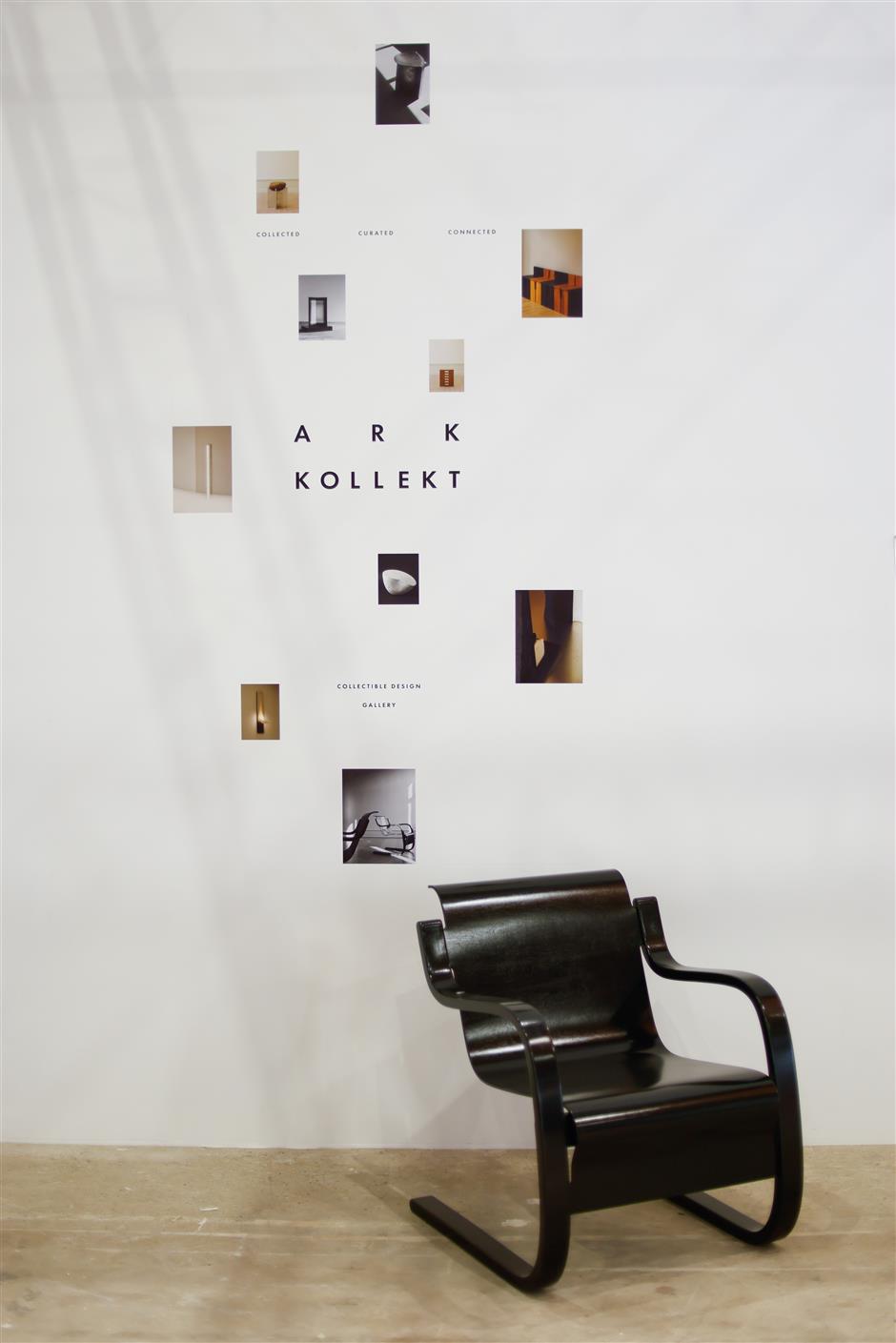

Inside West Bund Art Center, a vast former aircraft factory that now anchors Shanghai's Art Week, an oversized chair made of folded sheet metal stood like a monument to precision. Nearby, vintage furniture was cocooned in dough and sugar, aluminum walls melted into staged ruins, and 3D-printed objects shimmered with recycled plastic.

From November 13 to 16, the industrial hall hosted the second edition of design /delight 2025 – not a conventional furniture fair, nor a typical art show, but a hybrid platform positioned somewhere between a design exhibition and an art market.

But more than visuals, what the platform really staged was a question: Can collectible design become a real market in China?

Globally, collectible designs – unique or limited-run functional objects sold and presented like art – have found increasing attention among collectors, design galleries, and auction houses. From the US$3.42 million sale of a Jean Royère "Polar Bear" sofa at Christie's in 2021 to collectible chairs designed by Virgil Abloh for Vitra, the sector is gaining symbolic weight and speculative value.

Market research firms estimate the global design collectibles segment will grow steadily over the next decade, driven by high-net-worth interest, brand collaborations, and shifting consumer values.

China, where art collections are well-established, traditionally views design as either utilitarian or luxury-branded, leaving the category unfamiliar. That gap is precisely what design /delight attempts to bridge by importing international design voices, spotlighting experimental Asian studios, and most critically, testing whether objects that cannot be sat on can still be sold.

"People who truly connect with the work are often willing to invest in it," said Belgian designer Arthur Vandergucht, whose towering metal chair greeted visitors at the design /delight entrance. "Even if the pieces aren't inexpensive, they carry a presence that justifies it."

For Vandergucht, pricing is determined less by industrial logic than by a piece's ability to provoke physical and emotional responses.

"My pieces are precious, both in the process and in their presence," he said. His works, forged by hand and defined by clean construction lines, invite touch – yet refuse conventional function.

At design /delight, most small collectible works were priced between 10,000 and 100,000 yuan (US$1,400-14,000), while large, one-off pieces or site-specific installations could reach up to 500,000 yuan.

Those prices are between luxury furniture and entry-level art, rare but affordable compared to blue-chip contemporary art. Design /delight organizers say the pricing strategy is meant to attract both seasoned collectors and new buyers who may not buy paintings but are ready to "collect design."

In a market where value is still tied to function, brand, or name recognition, buying a chair you can't sit on or a lamp that prioritizes metaphor over light requires a mindset shift. Chinese designers exhibiting at the platform must sell and explain why their works matter.

"Our design culture is still evolving, still searching for a language that feels entirely our own," said Ellen Hu, founder of Haus of Hu. That sense of unfinished identity, however, is also where many designers find freedom. "We have the freedom to redefine what Chinese design can be – to build a new narrative grounded in our philosophy, materiality, and sensibility."

For design /delight, Hu collaborated with Theo Sykes & Dariia Nepop, presenting an architectural installation and a new furniture series centered on the domestic entryway, exploring it as a threshold between spaces.

Unicoggetto founder Zhao Zihan echoed the sentiment. "Functional art has deep roots in China," he said. "But its modern form is still emerging, and a stable, mature market has yet to follow."

Zhao's presentation, "Constructed Ruins," featured cast-aluminum pieces in organic forms staged within a ruin-like scenography, deliberately moving beyond the conventional "white cube" format to provoke a reconsideration of value between functional art and pure artistic creation.

Both designers see collectible design not only as a style but also as a strategy – one that rewards process, patience, and cultural inquiry. "The value of my work is never determined purely by price," said Hu. "It is shaped by time, process, and the intention behind each piece."

While some collectors remain hesitant to treat furniture as art, Zhao believes the landscape is shifting. "With the growing influence of design fairs and the emergence of more creators," he said, "I'm confident that this situation will continue to improve."

The path to a functioning Chinese collectible design market is uncertain for designers and buyers. Western collectors are increasingly aware of the artistic narratives in functional objects, but Chinese buyers often view design through utility or prestige branding.

"Many people still think design should be usable," said collector Chen Damin. "They often ask, 'Why would I pay for a chair that is not usable?'"

A longtime advocate for limited-run design, Chen himself collects selectively and sees the market potential, but he also acknowledges the cultural and educational gap.

"Collectors in China are used to valuing paintings or sculptures. For collectible design, we're still at the beginning."

In Case You Missed It...

![[China Tech] Local Experts Identify a New Cancer Target](https://obj.shine.cn/files/2026/01/09/f9083ef4-fea8-4a74-8547-5a243e39e8ad_0.jpg)