Flowers of Shanghai, Bliss on the Table – a Taipei Man's New Year in the City by the Sea

That New Year's Eve in Shanghai back in 2014 began with a walk into a dreamscape. Early that morning, my wife and I headed to the Shuangfeng Road wet market, stepping into a world where heavy snowflakes danced through the air. The streets were unusually hushed, the sparse traffic muffled by a white veil. But inside the market, the atmosphere shifted abruptly: it was a cacophony of voices, a teeming, vibrant crush of humanity – the very essence of nian wei (年味), the living breath of the New Year.

In Taipei, the Lunar New Year has gradually withered into a series of clinical conveniences – greetings sent via smartphone and the cold efficiency of supermarket aisles. Though the residual warmth of the three grand hearths in my ancestral home in Huwei, Yunlin (literally "the Tiger's Tail") still lingers in my memory, most of my adult life has been spent in the urban sterility of Taipei.

There, the holiday is less a ritual and more a precise rehearsal. One simply pre-orders a curated menu, picks it up, and reheats it. It is a grand meal, certainly, but one stripped of the soul of smoke and fire. It feels like an opera that skips the overture and rushes straight to the finale – efficient, yes, but devoid of the emotional crescendo that comes from anticipation.

It wasn't until years ago, when I followed my Shanghainese wife back to her hometown, that I rediscovered the true rhythm of the season inside a longtang (弄堂) – a traditional alleyway house where the air itself seemed seasoned with the scent of scallion oil and yellow rice wine.

Shanghai is, in many ways, more modern than Taipei, yet beneath its sleek exterior lies a stubborn adherence to the "handmade".

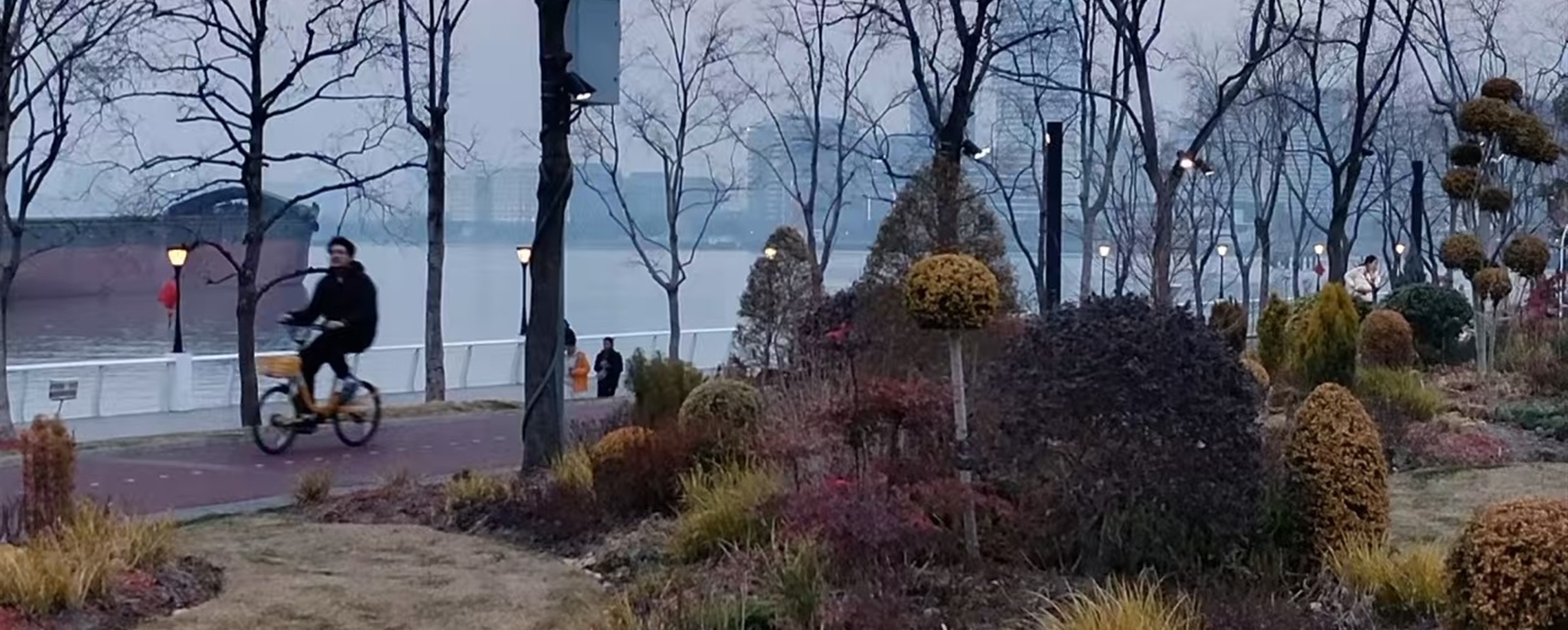

In the 12th lunar month, the Shanghai sky takes on a melancholic shade of blue-gray, and the damp cold has a way of boring into one's marrow. Along the boulevards, the French plane trees have shed their golden leaves, their bare branches etched against the sky in mid-winter desolation. It was only while weaving through the cramped stalls of the local market, amidst the jostling heat of the crowd, that I truly felt the "temperature" of the New Year.

In Taipei, I was the pampered "young master," accustomed to being served. But in Shanghai, I encountered a different breed of masculinity: the Ma Da Sao (买汰烧). A Shanghainese homophone for "buy, wash, and cook," it refers to the men who run the household.

In the longtang, it is often the sharp-suited office professionals who, on weekends, don pajamas and carry wicker baskets, expertly judging the lean-to-fat ratio of a slab of pork belly. Watching my male neighbors command their kitchens with such practiced ease, I had no choice but to retire my Taipei nonchalance and become a clumsy apprentice to my wife.

"Soak the jellyfish in cold water. Remember to change the water three times," she commanded without looking up, her cleaver thudding against the cutting board with the rhythmic precision of a metronome. I realized then that the legendary crunch of her scallion-oil jellyfish was not luck, but the result of a near-superstitious rigor regarding timing.

The banquet consisted of 12 dishes, all envisioned and executed by her. My sole contribution, aside from basic prep work, was the Dan Jiao (蛋饺) – egg dumplings.

Under the watchful eye of my 90-year-old Niang Niang (孃孃, aunt), who spoke in the melodic lilt of the Shanghai dialect, I began my lesson. She demonstrated two "textbook" dumplings before handing me the long-handled circular ladle. It was an exercise in monastic patience: left hand swirling the ladle over a gentle flame, right hand greasing the surface with pork fat. The pour of the egg wash met the heat with a soft hiss, forming a skin as thin as a cicada's wing. I tucked in the pork filling, used chopsticks to fold the golden veil over, and pressed the edges sealed.

My first attempt was surprisingly plump and beautiful. Niang Niang clapped with unbridled delight. As the golden, ingot-shaped dumplings piled up, I felt a surge of pride. These were more than just symbols of wealth; they were the only "handmade warmth" I contributed to the table.

We opened a bottle of Italian sparkling wine to begin. The golden bubbles rising in the flutes played against the frost outside, signaling the start of the cold appetizers. The Suzhou-style kao fu (烤麸), braised wheat gluten, is the foundational color of the Shanghai palate.

My wife insisted on tearing the gluten by hand, arguing that irregular edges soak up the "heavy oil and red sauce" more effectively. Sautéed with shiitake mushrooms and wood ear fungus, every bite was a tribute to the Jiangnan heartland.

However, the real revelation was the hand-shredded Man Xiang (鳗鲞) – dried eel. Growing up on an island, I associated fish with silver scales and springy flesh. This was something else – the "soul flavor" brought to Shanghai by Ningbo immigrants. A massive sea eel is split down the spine, lightly salted, and then surrendered to the dry, biting northwesterly winds of winter. When the wind-cured eel is steamed with yellow wine, it releases a pungent, primitive fishiness that made me recoil.

"This is Xian Xian (咸鲜) – the savory-freshness," my wife said with a confident smile. "Dip it in vinegar, and you won't be able to stop."

She was right. Once the skin and bones were removed and the white flesh was dipped into the deep, dark Zhenjiang balsamic, all my prejudices dissolved. It was a flavor forged by time and pressure – a taste of the sea, concentrated and weathered. Some of life's most profound joys, it seems, must undergo a period of drying and suppression before they can be fully realized.

Then came the "Ruyi" dish, stir-fried soybean sprouts. Shaped like ancient scepters of luck, they were the palate cleanser after the eel, a reminder that life, however complex, ultimately seeks the simple peace of "having everything as one wishes".

As the hot courses arrived, the kitchen became a sanctuary of steam. The Ta Ku Cai (塔苦菜) – a dark, flat winter green rarely seen in Taipei – tasted bitter at first, then finished with a lingering sweetness. Having endured the frost, it had transformed its struggle into sugar – a fitting philosophy for the Shanghainese life.

The Shui Sun (水笋), water bamboo shoots, braised with pork belly offered a bridge to my home across the strait. My wife insisted on braising it until the fat had completely surrendered to the fibers of the bamboo. Watching the pot bubble, I thought of the bamboo shoot and pork belly stews of my childhood in Taiwan. This craving for the marriage of fat and fiber is perhaps the most stable emotional common denominator between our two shores.

The centerpiece was the Suzhou-style huo guo (火锅), hotpot. In a Shanghai winter, this pot is more than a vessel; it is the center of the family gravity.

Niang Niang recalled the old days of purple copper pots fueled by charcoal. Today, we use a clay pot on a gas stove, but the logic of the layers remains sacred. At the bottom lies a foundation of napa cabbage and glass noodles to soak up the essence. Above them, a symphony of ingredients is orchestrated: springy fish balls, gelatinous tendons, sweet scallops, velvety sea cucumber, and thick shiitake mushrooms. And there, crowning the arrangement like shining gold ingots, were my handmade egg dumplings.

Unlike the chaotic "toss-as-you-go" hotpots of Taipei, this was a dish of pre-ordained order. As the rich hen broth was poured in and the flame brought the liquid to a simmer, the ingredients achieved a slow, collective reconciliation. The steam blurred the cold world outside, and I realized that the pot was a metaphor for the family itself: the humble, supportive base; the distinct, colorful members in the middle; and at the top, the golden hopes for the future.

The meal concluded with two desserts: crispy, golden spring rolls dipped in vinegar, and an "Eight-Treasure Rice" from the venerable Qiaojiashan – a glistening mound of glutinous rice and lard-moistened bean paste that melted away the last of the sparkling wine.

Looking back on that night, there were no firecrackers, yet the 12 dishes created a sense of wholeness that no explosion could match. In Taipei, I sought a life without "trouble". In Shanghai, I learned that the trouble itself is a form of love. Those 12 dishes didn't just fill our stomachs; they redefined my understanding of the New Year.

The holiday isn't about eating the pre-ordered fish; it's about the "busy-work," the smoke of the kitchen, and the mutual respect for life found within the ritual. This feast – stretching from my childhood memories in Huwei to its blooming realization in Shanghai – remains the most profound scripture on home and tradition I have ever read.

(The author, who earned a PhD in linguistics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, is a professor of English and college dean at Sanda University, Shanghai.)

In Case You Missed It...

Popular Reads

Flowers of Shanghai, Bliss on the Table – a Taipei Man's New Year in the City by the Sea

Hospital activates critical pediatric transfer teams during holiday period

Celebrate the Year of the Horse with Star-studded Galas and Citywide Cultural Activities