Inside 'Suicide Pact' Chat Groups, a Father Tries to Pull Teenagers Back

"I'm heading out first."

In the dim glow of his phone screen, the message flashed briefly in a chat group called Yuesi (约死), slang for a "suicide pact."

Xu Shihai replied almost instantly: "I've had enough of living, too. Could you take me with you? I'm scared."

To most people, the exchange would have looked like two hesitant teenagers talking online.

Few would have guessed that behind those words was a father who had lost his son.

He lost a child

Xu Shihai, 45, hails from Nanyang in central China's Henan Province, but moved to Zhengzhou at a young age.

In May 2020, his 17-year-old son jumped to his death from their apartment.

"There were no warning signs," Xu told Phoenix New Media. "Around three or four in the morning, security guards knocked on my door to inform me of his death."

The night before, the boy had brought his father a glass of water while doing laundry. They had plans to go fruit-picking together the following day.

"It was May. I was sitting outside in the sun," Xu said. "But I felt cold all over."

Later, Xu went through his son's phone and discovered that, in the hours before his death, the boy had repeatedly watched an animated series and appeared to have emotionally immersed himself in it.

"He slipped into the character," Xu said. "When he left, he was dressed just like the protagonist – a white top and black pants. But I think that was only a trigger, not the reason."

What Xu found in his son's diary was more devastating.

The boy had not acted on impulse. He had been trapped for a long time in a cycle of depression, frustration, and self-denial.

"He wrote about a girl he liked – she was outstanding and got into a good school. He didn't. No matter how hard he tried, his grades stayed the same," Xu said. "I believe my son was depressed. Severely depressed."

As Xu tried to make sense of what had happened, he discovered that his son had joined multiple online chat groups. One of them, called Yuesi, caught his attention – and pulled him into a world he had never imagined.

These were online groups where people gathered to plan their deaths.

Xu learned that such groups often began as large chat rooms for venting about grades, parents, and teachers. Over time, they fractured into smaller groups. In those spaces, academic talk disappeared, replaced by pure complaint, as negative emotions fed on one another.

Eventually, a final group would emerge: a "suicide pact" chat. Members stopped talking altogether. They only set a time, a place, and a way to die.

"What shocked me most," Xu said, "was how easy giving up on life had become for these kids."

A water rescuer who went underground

Besides being a home renovation worker, Xu has another identity: he is a volunteer with the Zhengzhou Red Cross water rescue team.

Accustomed to retrieving drowning victims from rivers and lakes, Xu decided after his son's death to enter what he calls a deeper, darker body of water – the Yuesi chat groups.

It was anything but simple.

Inside the groups, language functioned like code. Burning charcoal was called "barbecue." Jumping into a river became "diving." Jumping from a building was "going clubbing."

To blend in, Xu learned how the children spoke. He pretended to be a 12- or 13-year-old student.

"I'd say things like, 'I've had enough of living, but I'm a coward – could you take me with you?'" he explained. "That's how they'd pull me into the smaller groups."

Once inside, Xu often sent a small digital red envelope – typically about 50 yuan (US$7).

"Sending money usually keeps you from being kicked out," he said. "It lets you stay."

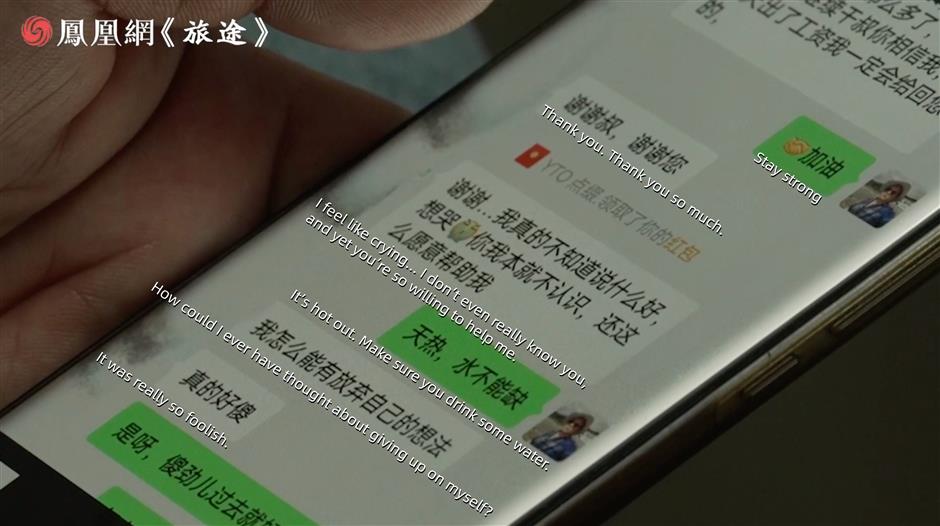

From there, he added some of the children as contacts and began talking privately, building deeper connections.

"Once they open up," Xu said, "there's a chance to pull them back."

If a child was not in immediate danger, Xu focused on ordinary conversation – what they ate, whether they went out that day, a stray cat on the street, a small flower by the roadside – anything to establish trust and respond quickly when emotions spiked.

But when a child was on the verge of acting, Xu did not try to reason.

He stalled. Distracted. Bought time.

In one case, a child was already standing on a rooftop. Xu pretended to ask the child to "take him along," urging him to send photos to confirm the location. He asked for retakes, quietly scanning for landmarks, while alerting friends to call the police. He kept chatting until officers arrived.

That night, five children – all aged 13 or 14 – were pulled back.

In another case, a child was standing on a bridge, preparing to jump. Xu did not argue. He first guided the child away from immediate danger, then slowly drew him back from the emotional edge.

"Sometimes," Xu said, "life and death are separated by just one useless sentence."

There were children he couldn't hold onto.

One year, Xu received messages in a single day that three teenagers he had spoken with for months were "gone."

That night, he sat by the roadside with a friend and cried uncontrollably.

"It feels like farming," he said. "You do everything you can to protect a seedling, and then one sudden storm takes it away."

Why they want to die

Among the children Xu has encountered, academic failure is the most common trigger.

"At least 80 percent," he said. "Some parents completely lose control over a single exam, saying things like, 'I don't want to live anymore.' What do you think the child hears? If they can't survive the present, where does this 'happy future' come from?"

Other factors include romantic heartbreak, bullying, and emotional isolation, especially among so-called left-behind children, whose parents work far from home.

"Many rural children grow up with grandparents," Xu said. "Older people don't understand the world these kids are exposed to or how to help them. Over time, the child feels no one understands them – no care, no love."

According to the World Health Organization, depression is estimated to occur among 1.3 percent of adolescents aged 10-14 years globally, and 3.4 percent of those aged 15-19. In China, the prevalence of adolescent depression stands at around 2 percent, the National Health Commission reports.

Yet only a tiny fraction of these young people receive sustained, systematic support.

Inside Yuesi groups, negativity is amplified – shifting from venting and complaint to mutual confirmation and encouragement.

When "should we go or not" becomes a collective choice, individual fear begins to dissolve.

In some groups, adults lurk as well, actively encouraging vulnerable minors to kill themselves.

"They tell them, 'The world is wrong, not you. You're pure. You were born at the wrong time," Xu said. "'You have to reboot yourself to become stronger, and change the world.'"

Xu believes these adults derive twisted psychological satisfaction from manipulation. "It's brainwashing – playing with other people's lives," he said. "Afterward, they'll say things like, 'I've helped another batch cross over.'"

Letting go, letting others step in

People often ask what happens after children are saved.

Not everyone stays in touch, Xu said.

Some graduate, find jobs, and still send a message now and then: How are you, uncle? Others slowly disappear – sometimes deleting him altogether.

"That's fine," Xu said. "It means they've moved on."

In recent years, Xu has spent less time monitoring the groups – not because he has stopped caring, but because he knows he also needs protection.

"I can't afford it anymore," he told Phoenix New Media. "If I keep going like this, something will happen to me, too."

Yet his persistence has drawn others in. More volunteers have joined the groups; some continue his methods, while others build more professional support networks.

"It's comforting," Xu said. "The number of volunteers has grown exponentially. It used to be just me."

On October 24, a public-interest film based on Xu's real-life story, "A Journey of Blossoms," was released, bringing wider attention to adolescent mental health.

"I don't think I did anything special," Xu said. "It was just a coincidence. Someone needed help, and I happened to be there."

Xu now hopes to establish a small workshop – a place to talk with parents about how to communicate with their children before loss turns into a lifelong question of why.

He once said he hoped children could live like wild grass – not carefully cultivated flowers, but something that could still find light even through cracks in concrete.

For a father who has already lost a child, it is the only wish he still knows how to hold onto.

In Case You Missed It...

![[First in Shanghai] Tradition Reborn, Futures Imagined in Shanghai's Latest Landmark Openings](https://obj.shine.cn/files/2025/10/21/8ec623dd-7e34-429a-805d-75886e1e16d7_0.png)