China's Printed Circuit Boards Underpin Tech Revolution

SinoArk

This column intends to take deep dives into how today's industrial change is being woven by China – its factories, markets, and clusters that provide the threads. Each story will follow a cast of people and companies – engineers and founders, suppliers and shop-floor managers – whose daily choices animate China's innovation engine. We tell their stories closely, in human scale, and then pull back to read the larger weave: How domestic design, scale and supply-chain craft ripple outward and reshape industries across continents.

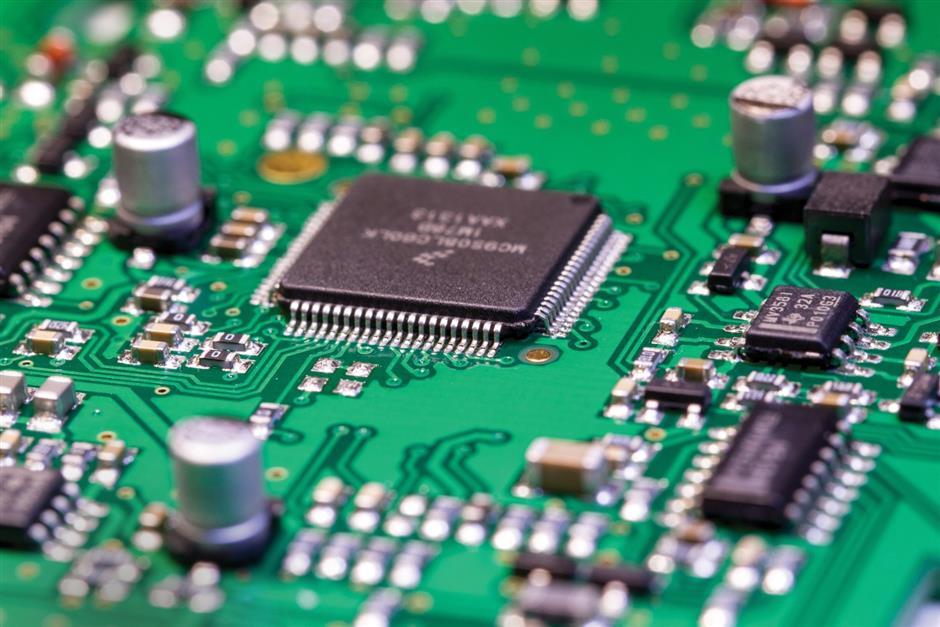

If you pry open almost any gadget – a smartphone, a factory sensor or a humming server in a large data center – you'll see a slab of fiberglass and copper, usually green but sometimes blue or red, that is studded with tiny metallic veins. Chips sit on it like cities connected by roads. That is a printed circuit board, the quiet backbone of the electronic world.

Electricity running through the board brings silicon to life. If semiconductors are the brains of technology, printed circuit boards are its skeleton and nervous system, routing signals, delivering power and holding everything together. It is the platform on which every electronic component performs. Without it, even the most advanced semiconductors would be useless.

Chips may capture all the headlines, but the real story in the technology revolution, at least for now, begins on the board beneath them.

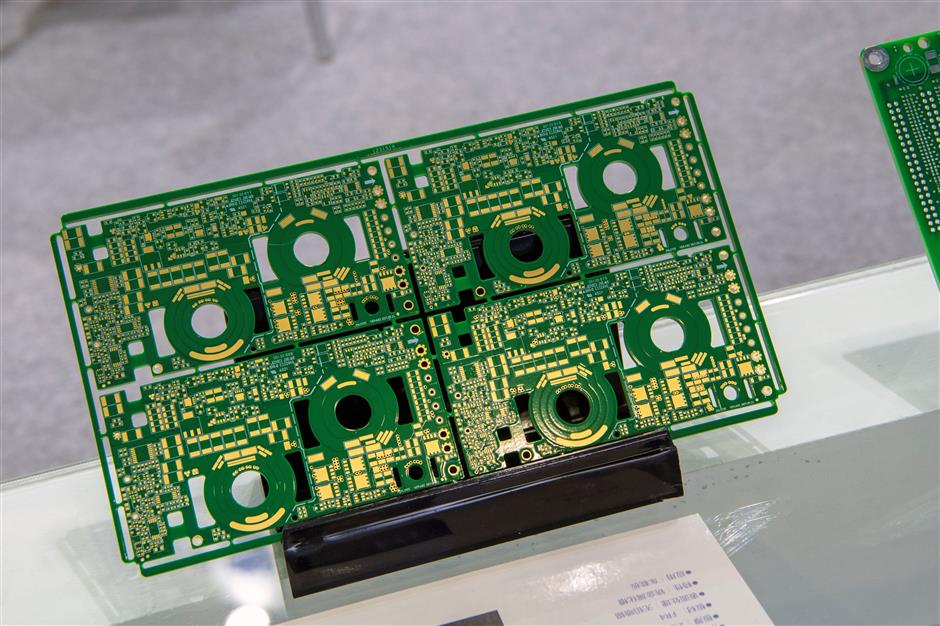

Printed circuit boards are single or multilayer copper-etched boards that carry signals between chips and peripherals. But their complexity varies wildly. A single-sided board for a toy is one thing; an 18-layer backplane that routes signals between graphics processing units in an AI server is quite another.

Concentric circles of development

The industry map has been developed in concentric growth circles over the past four decades.

In the first wave of consumer and mobile electronics (1980-2020s), they were produced for radios, personal computers and then smartphones in highly standardized volumes with low-cost margins.

In the 1990s into the first decade of the new century, as computing spread in electrification, driver-assisted vehicles and industrial controls, multilayer boards proliferated in motherboards and networking gear, demanding better materials, tighter tolerances and higher standards of reliability.

Today, with the advent of cloud computing and AI data centers, so-called high and ultra-high density boards are required, featuring more layers and substrates that enable chips to communicate at higher speeds and densities.

But progress doesn't end there. There is an emerging industry in rapid prototyping, small-batch services that lower costs for hardware startups and research labs. The new era requires more designs and more boards to creating a reinforced cycle of faster electrification and digitalization.

Until recently, printed circuit boards were largely a cost and logistics problem for original equipment manufacturers: Buy the right board at the right price and move on.

However, that calculus has changed for two reasons. First, the technical horizon shifted. High and ultra-high density interconnect boards are not commodity items. They need precision drilling, advanced laminates and painstaking process control. Secondly, demand has spiked from cloud computing operators and AI companies for servers and networking gear.

China's rise to prominence

China has become the world's largest maker of printed circuit boards. US industry representative David Schild, in testimony before the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission in 2025, said China produces well over half of the world's printed circuit boards, including most of the high-density types used in advanced computing systems. He wasn't telling the public anything that the industry didn't already know.

Data collector Wind last September said the printed circuit board sector on China's CSI stock index had surged 150 percent in six months. Shares in Shennan Circuits, which trades on the Shenzhen market, soared fourfold over a year, and Victory Giant Technology hit a market cap approaching 300 billion yuan (US$43 billion). Investors see them as enablers of the AI revolution, the hidden scaffolding of data centers and electric vehicles.

The ascendancy of China's printed circuit board industry resulted from decades of intersecting factors: policy choices, geography and what engineers call "the grind."

A legendary moment came in 1981, when Shanghai Radio Factory No. 20, tasked with supporting China's ambitious new color TV project, spent US$3 million on an automated production line from Japan's Niigata Iron Works. When the first machine-etched 0.3mm-wide circuits rolled off the line, veteran engineers reportedly wept. The leap from hand-drawn imperfection to industrial precision was a profound milestone.

But the true catalyst came in the 1990s, when Taiwan technology companies, facing soaring labor costs, looked to the Chinese mainland as the new frontier.

Although island authorities blocked transfer of what they considered "industrial crown jewels," they didn't categorize printed circuit boards among "critical" high technology. That opened the floodgate for mainland production, led by companies such as Unimicron, Tripod and Compeq.

Between 1992 and 2013, over 200 Taiwanese firms set up shop on the mainland, accounting for 70 percent of China's entire output of printed circuit boards.

The output transformed the industrial landscape in the Pearl River and Yangtze River deltas into the most potent manufacturing clusters in the world.

China's relentless climb to the top of the printed circuit leader board was unstoppable. In 2003, Chinese production surpassed that of the US, dethroning Japan three years later. By 2021, one of ever printed circuit boards on the planet was made in China.

Behind the numbers lay legions of engineers, quality specialists and materials scientists. "Printed circuit boards are a low-margin business that rewards process mastery and engineering discipline," said Jian Lian, analyst from the Citic Foundation in China.

Spillover effects

The expertise honed in the industry spilled over into adjacent sectors, from electronics assembly to chip packaging and even precision equipment manufacturing. That has made it difficult for global supply chains to quickly "replace" China's capacity through policy incentives alone.

Companies in the printed circuit board industry have a strong story to tell, and investors are listening. Victory Giant Technology, founded in 2006 as a modest supplier, is now planning to go public on the Hong Kong stock exchange, leveraging its position in Nvidia's supply chain.

Guangzhou-based Houde Electronics isn't far behind. Founded in 1991 by Wu Ligan, who arrived from Taiwan with US$30 million to spend, the company has grown from a contract manufacturer into a global leader in high-end printed circuit boards, with more than 81 percent of its revenue from overseas markets and a valuation of more than 150 billion yuan.

The sector has always pushed the technological envelope. Shennan Circuits is a case in point. Founded in 1984 to serve the development of China's telecommunications industry, the company never took its eye off moving up the value chain. In 2006, it could manufacture a 42-layer board – a complex feat. By 2019, deep spending on research and development delivered an astonishing 120-layer board.

Not every printed circuit board story is about 18-layer server backplanes, however. One of the lower-profile consequences has been the rise of rapid prototyping.

From bazaar shops to global users

At the turn of the century, Hong Peifeng, head of intelligent automation at JLC Group, recalls how electronics bazaars in Shenzhen teemed with small design shops, each striving for prototype printed circuit boards. Today, after pooling those resources, JLC has cut prototyping costs from thousands to less than US$10 and lead times to 12 hours from weeks.

Chinese companies democratized hardware innovation on a global scale. Suddenly, a college student in a dorm room in Ohio, a startup in a garage in Bangalore or an artist in a studio in Berlin had access to the same rapid, affordable prototyping capabilities as a Silicon Valley giant. This is the profound, often overlooked, spillover effect of China's manufacturing miracle. Its relentless pursuit of efficiency has lowered the barrier to creation for everyone.

The industrial effect is tangible. Unitree Robotics – which rose to prominence after a Spring Festival Gala TV performance – completed five design iterations and multiple sample validations in three months using JLC's one-stop prototyping and assembly services. Faster, cheaper prototypes have turned hardware development from a costly gamble into a routine engineering practice.

JLC turned operational efficiency into a platform. Its Open Hardware community now counts over 800,000 monthly active users, more than 100,000 open projects and some 30,000 quality engineering contributions, feeding a pipeline from open designs to paid manufacture. Commercially, JLC serves customers in more than 180 countries with overseas revenue comprising almost 19 percent of core revenue.

In this dizzying rise to prominence, China's printed circuit board industry, one simple truth stands out. The once inobtrusive work of making copper tracks on a piece of fiberglass has led Chinese companies into global markets, boardrooms, research labs and consumer purchases. And its legacy continues into new frontiers.

(The author specializes in the international expansion of Chinese tech companies in the advanced hardware and energy sectors. He also serves as a geo-economic expert for several think tanks in Beijing.)

In Case You Missed It...

![[China Tech] FDA Clears Gene-Editing Trial for Corneal Dystrophy at Fudan University Hospital](https://obj.shine.cn/files/2026/01/19/a89feb4b-baec-499e-a03b-7d44042cb364_0.jpg)