How China Responded to Shenzhou-20's Window Crack: Launching Its First Emergency Space Mission

China's first emergency space launch began with something barely noticeable: a small triangle-shaped mark on a window of the Shenzhou-20 return capsule.

On November 5, one day before the planned return of the Shenzhou-20 crew, astronauts conducting routine checks discovered the mark on the edge of a capsule window.

The crew – Chen Dong, Chen Zhongrui and Wang Jie – had been in orbit for over 180 days and had just completed a handover with the newly arrived Shenzhou-21 astronauts at China's orbiting Tiangong space station.

The astronauts took photographs from various angles, and the station's robotic arm captured images from outside. Ground engineers reviewed these images and quickly identified the mark as a full-thickness crack.

Jia Shijin, chief designer of China's manned spacecraft system, stated on China Central Television that the shape "looked like a small triangle." The team was surprised, as the likelihood of debris striking that precise spot in space is relatively low.

As a precaution, mission controllers postponed the return for 12 hours to ensure safety.

Shenzhou windows feature a three-layer design, with the outer layer serving as part of the heat shield. Jia explained that a crack posed a higher risk during re-entry to the atmosphere, where temperatures can exceed 1,000 degrees Celsius.

Simulations and wind-tunnel tests showed the crack could expand, potentially damaging internal seals and compromising cabin pressure.

After checking past data, engineers concluded the design had no flaws and that a tiny piece of space debris, likely less than one millimeter wide, was the probable cause.

By November 8, the capsule was declared unsafe for carrying astronauts back to Earth.

"It came very suddenly," said Ji Qiming, assistant director and spokesperson for the China Manned Space Agency.

"But it was already covered in our contingency plans. When needed, we have procedures in place to respond," Ji told CCTV.

That assessment came as the station hosted six astronauts from the two crews. The Shenzhou-21 return capsule remained available with three seats.

Supplies on the station were stable because the life-support system recycles water and produces oxygen through electrolysis.

Food stocks were also sufficient for two full crews. The astronauts continued experiments and trained for possible changes to the return plan.

"Shenzhou-21 did not only carry food for its crew; it also brought reserve supplies," said Wu Dawei, deputy chief designer of the astronaut system at the China Astronaut Research and Training Center.

"We even sent up a hot-air oven, similar to an air fryer on Earth, so both crews could share freshly prepared meals. A few extra days' worth of food is not an issue," Wu added.

Mission planners explored two options: either launch Shenzhou-22 first to restore backup capabilities or return the Shenzhou-20 crew immediately using Shenzhou-21.

Launching first would necessitate moving another vehicle to free up a docking port. In contrast, returning first posed fewer operational risks and reduced the astronauts' waiting time, leading planners to approve that plan, said Ji.

On November 10, China activated its emergency protocols. The Shenzhou-20 astronauts began preparations for their return using the Shenzhou-21 spacecraft.

Meanwhile, at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in northwestern Gansu Province, teams initiated a compressed 16-day schedule to prepare the unmanned Shenzhou-22 for launch.

The teams completed tasks that would typically take several days in consecutive shifts. Managers maintained quality control measures while minimizing rest periods to meet the deadline, Ji recalled.

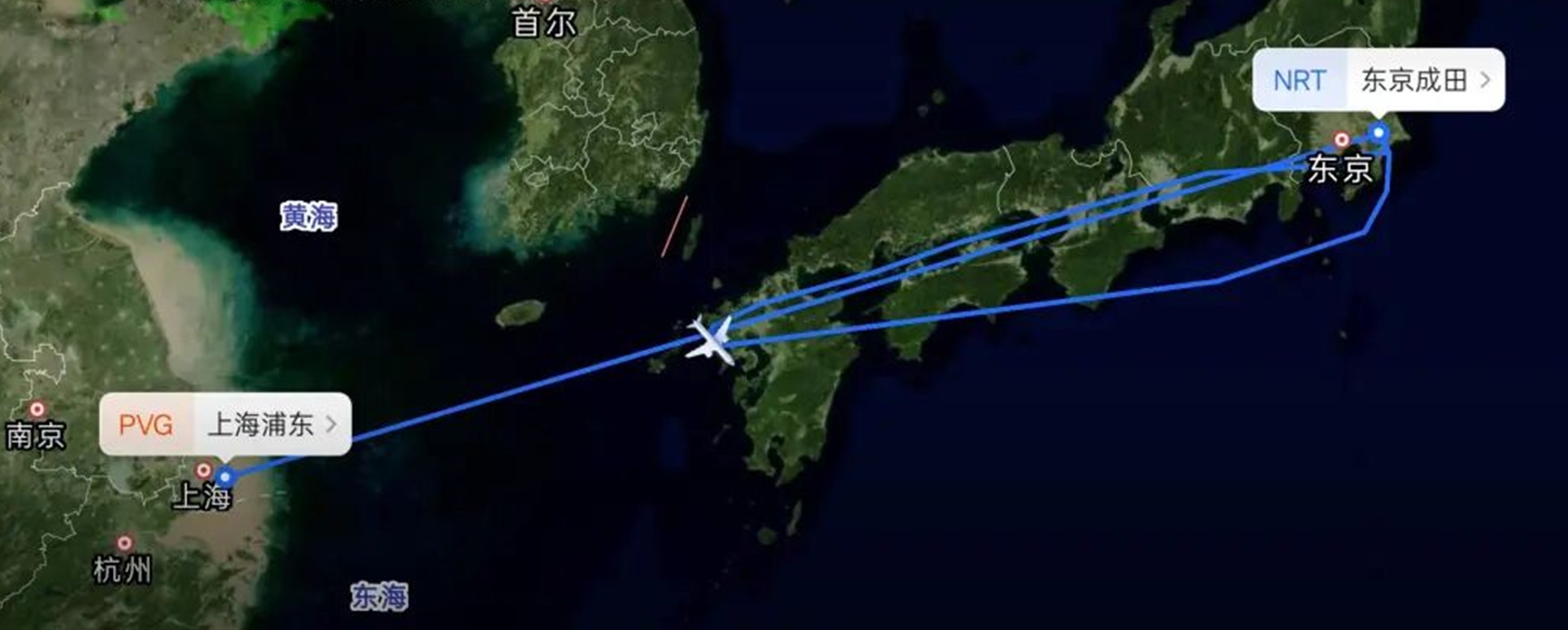

On November 14, mission control instructed Shenzhou-21 to undock from the Tiangong space station.

The spacecraft carried three Shenzhou-20 astronauts and four laboratory mice that had exceeded their planned experimental timeline. To support the animals during the delay, the astronauts used some of their water and soybean milk.

After passing through the communications blackout zone, the ship reestablished contact, and controllers confirmed that the astronauts were in good condition.

The capsule landed at 4:40pm on November 14. Recovery teams quickly located it, and the astronauts exited in good health.

The crew spent 204 days in orbit, setting a new record for the longest duration of a single Chinese mission. Chen Dong became the first Chinese astronaut to spend more than 400 days in space.

With the crew safe, the mission progressed to the next phase. On November 25, the unmanned Shenzhou-22 was launched, carrying supplies, medical kits, fresh vegetables, fruits and a special device designed to reinforce the cracked window on Shenzhou-20.

The spacecraft docked with the station in 3.5 hours. Using external keys kept on the station for emergency scenarios, astronauts opened the spacecraft's hatch.

Shenzhou-20 will return later without a crew so that engineers can collect real re-entry data. The results will guide future improvements as the amount of space debris in low Earth orbit continues to increase.

The incident also created a gap in China's crew numbering sequence. Since crew names correspond to their spacecraft numbers, there will be no "Shenzhou-22 crew" recorded.

"The empty designation will serve as a reminder that even after many successful missions, risks in space operations remain, and standards must stay high," said the chief designer, Jia.

In Case You Missed It...